Book contents

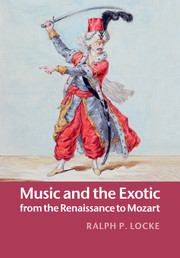

- Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

- Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Music examples

- Book part

- Notes to the reader

- Part I Introduction: a rich and complex heritage

- Part II The West and its Others

- Part III Songs and dance-types

- Part IV Exotic portrayals on stage, in concert, in church

- Afterword: A helpfully troubling term

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015

- Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

- Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Music examples

- Book part

- Notes to the reader

- Part I Introduction: a rich and complex heritage

- Part II The West and its Others

- Part III Songs and dance-types

- Part IV Exotic portrayals on stage, in concert, in church

- Afterword: A helpfully troubling term

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart , pp. 394 - 444Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015