Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

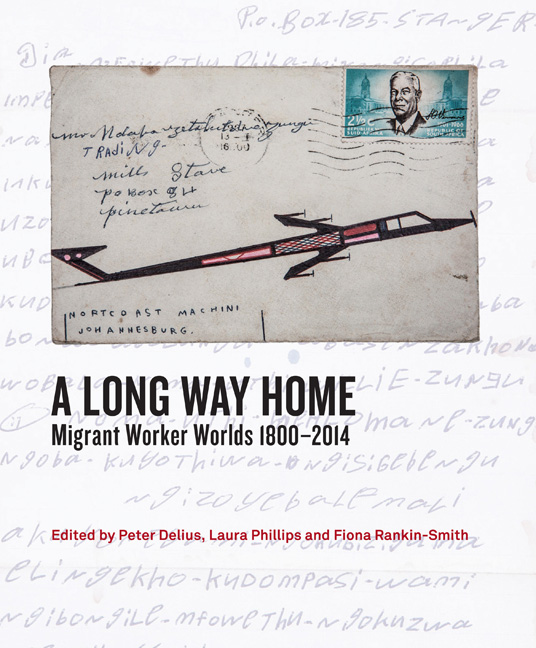

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Chapter 7 - The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Summary

South Africa's gold mines have always been dangerous. In addition to traumatic injuries, they have particularly high rates of the dust-induced lung disease, silicosis. The Commission into Safety and Health in the Mining Industry of 1995 found that dust levels were hazardous and that they had probably been so since the 1940s. This conclusion is unsurprising given the high silica content of the host ore, the depth of the mines, their reliance upon migrant labour and the racialised work regimes that characterised most of their history. Recent research puts the silicosis rate in living miners at between 22 and 30 per cent. Jill Murray's postmortem data estimates that up to 60 per cent of miners will eventually develop what is a life-threatening and untreatable disease.

The mines have also played a role in the spread of tuberculosis, a well-known consequence of exposure to silica dust. The incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa is currently among the highest in the world, with the infection rate among gold miners being ten times higher than for the general population. The majority of miners are migrant workers, which has resulted in the transmission of disease to rural communities and across national borders. There is strong evidence, stretching back to the 1920s, that South Africa's mines have spread tuberculosis to neighbouring states.

The fact that miners with lung disease have not been able to gain compensation lies behind the litigation currently before courts in Johannesburg and London. The cases against Anglo American, Gold Fields and Harmony, which are now into their tenth year, may eventually involve hundreds and thousands of miners and their surviving families. One British financial analyst has put the potential payout at $US100 billion, making it the largest class action of its kind.

In light of the current litigation, it is surprising that for most of the twentieth century South Africa's gold mines were believed to lead the world in the prevention of silicosis or miners’ phthisis, the oldest and most intractable of the occupational diseases. The major reason was the data presented in the annual reports of the Miners’ Phthisis Medical Bureau (the Bureau), the body responsible for awarding compensation and for collating the official data. In the period 1917 to 1920, for example, the silicosis rate among white miners was stated to be 2.195 per cent. By 1935, it had fallen to 0.885 per cent.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Long Way HomeMigrant Worker Worlds 1800–2014, pp. 106 - 115Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014