Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

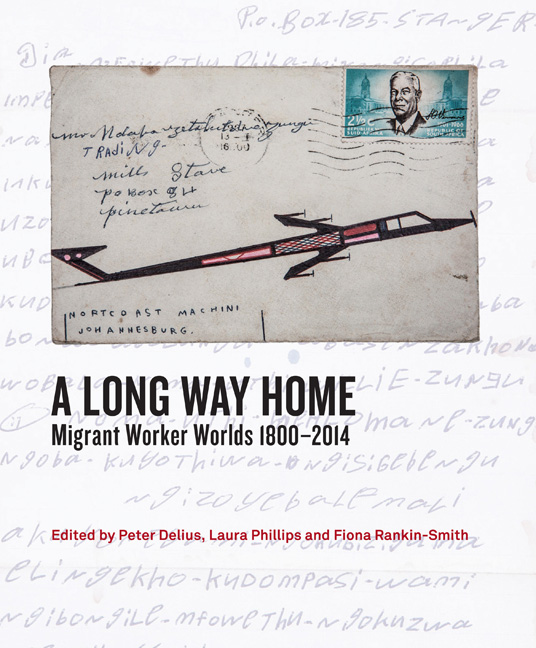

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Chapter 6 - The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Summary

During the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, black women in the rural areas of South Africa were largely subject to the authority and control of their male relatives: fathers, brothers, husbands and sons. They bore children for their husbands’ lineages, did most of the gardening and crop production, cooked and raised children till they were old enough to be initiated as men and women, or join adult age grade regiments. Under this system, there was a clear separation of labour – men worked with iron, carved wood, hunted and prepared animal skins for making clothing. Thus sewing was generally associated with men before the advent of European settlers, traders and missionaries brought cloth, metal needles, cotton thread and, most notably, beads into the rural context. Missionaries introduced sewing classes for women, who became the main producers of cloth dress and beadwork in a very short time. By 1850, beadwork was established as a female occupation/craft/art among black peoples on the east coast of South Africa, a praxis that spread inland with the beads.

Ironically, many writers have presented the production and wearing of beadwork as ‘traditional’ among many southern African black communities, but researchers have shown that beadwork, on the scale that emerged in the nineteenth century, was only possible with the provision of the necessary materials by Western traders. Southern African beadwork was thus an invented indigenous tradition and was not of any great age. The use of small glass beads to make intricate beaded items (as opposed to simple strings of beads) started at the end of the eighteenth century, but there was a much greater florescence of complex forms in the latter part of nineteenth century. From around 1840, women invented or adapted techniques that allowed them to develop new forms, possibly in response to the disruptions in traditional social orders that followed the introduction of a cash economy. These included men's recruitment into migrant labour and the resultant pressure on women to uphold tradition and were reflected in the ‘traditional’ objects that they made. These forms were new, but they quickly became ‘traditional’ and were treated as markers of ‘tradition’ by the people who made and wore them.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Long Way HomeMigrant Worker Worlds 1800–2014, pp. 89 - 105Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014