NASHVILLE Contra JAWS, or “The Imagination of Disaster” Revisited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 January 2021

Summary

Psychology knows that he who imagines disasters in some way desires them.

Theodor Adorno, Minima MoraliaJune 1975 – six weeks after Time headlined the fall of Saigon as ‘The Anatomy of a Debacle’ and wondered ‘How Should Americans Feel?’ – two movies opened, each in its way a brilliant modification on the current cycle of ‘disaster’ films that had appeared with Nixon II and were now, at the nadir of the nation's self-esteem, parallelled by the spectacular collapse of South Vietnam and unprecedented Watergate drama.

The multi-star, mounting-doom, intersecting-narrative format of Hollywood extravaganzas like EARTHQUAKE and THE TOWERING INFERNO (both 1974) was, as Robin Wood noted at the time, elaborated on and politicized in Robert Altman's NASHVILLE. But as NASHVILLE, the movie widely regarded as Altman's masterpiece, could be said to deconstruct the disaster film, so Steven Spielberg's Jaws would give the cycle a heightened intensity and, perhaps, a second lease on life.

Of course, cine-catastrophe was scarcely a new concept. It was only the movies, Susan Sontag had observed ten years earlier in ‘The Imagination of Disaster’, that allowed one to “participate in the fantasy of living through one's own death and more, the death of cities, the destruction of humanity itself”, Sontag argued that the armageddon-minded science-fiction films that enlivened drive-in screens in the period between the Korean and Vietnam wars were not about science at all but rather the aesthetics of destruction, the beauty of wreaking havoc, the pleasure of making a mess, the pure spectacle of “melting tanks, flying bodies, crashing walls, awesome craters and fissures in the earth”.

In the Sixties, the aesthetic of destruction was globalised: After CLEOPATRA (1962) nearly capsized an entire studio, Arthur Penn created the doomsday gangster film and Sam Peckinpah the disaster western. NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968), the most apocalyptic horror movie ever made in America, circulated for several years to achieve full cult status in early 1971 with a late-night run in Washington DCthat inexorably spread to other cities and college towns. (In New York, the film ran continuously as a midnight attraction from May 1971 through the following February and then again for 34 weeks following Nixon's re-election to July 1973.)

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

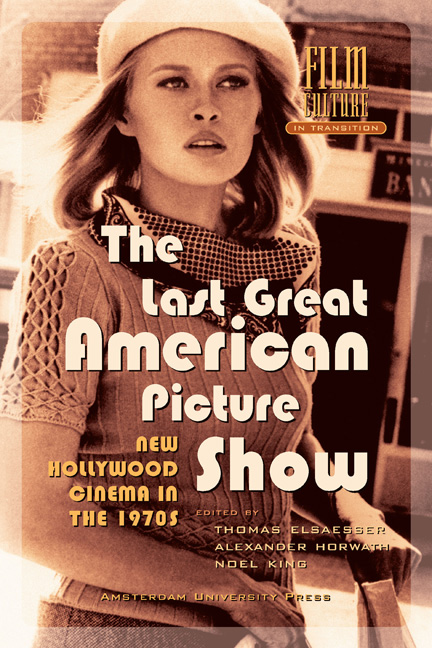

- The Last Great American Picture ShowNew Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s, pp. 195 - 222Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2004