American Auteur Cinema: The Last – or First – Great Picture Show

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 January 2021

Summary

For many critics writing in the 1980s, when Hollywood once more began to conquer the world's screens with its blockbusters, the American cinema they loved and admired – the cinema of the great studio directors as well as that of independent-minded auteurs – had entered its terminal decline. Not only was the industry that produced these new event movies different: so were the people who made them, the shoot-them-up plots that obsessed them, the special effects that enhanced them, and the money that drove them. Article after article mourned the ‘death of cinema’ and poured scorn on those who had ‘killed Hollywood’.

The retrospective vanishing point from which these critical obituaries were written was located in the early 1970s. Especially the years between 1967 and 1975 became the Golden Age of the ‘New Hollywood’, beginning with BONNIE AND CLYDE (Arthur Penn, 1967), THE GRADUATE (Mike Nichols 1967), Easy RIDER (Dennis Hopper/Peter Fonda, 1968) and ending with Roman Polanski's CHINATOWN (1974), Martin Scorsese's TAXI DRIVER (1975) and Robert Altman's NASHVILLE (1975). Coincidentally or not, these were also the years of the most violent social and political upheavals the United States had experienced for at least a generation, and probably not since the Depression in the mid-1930s. Between the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968, and Richard Nixon's resignation in August 1974, America underwent a period of intense collective soul-searching, fuelled by open generational conflict, and no less bitter struggles around what came to be known as ‘race’ and ‘gender’. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and the emergence of feminism gave birth to an entirely different political culture, acutely reflected in a spate of movies that often enough were as unsuccessful with the mass public as they were audacious, creative and offbeat, according to the critics. The paradox of the New Hollywood was that the loss of confidence of the nation, its self-doubt about ‘liberty and justice for all’ in those years, did little to stifle the energies of several groups of young filmmakers. They registered the moral malaise, but it did not blunt their appetite for stylistic or formal experiment.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

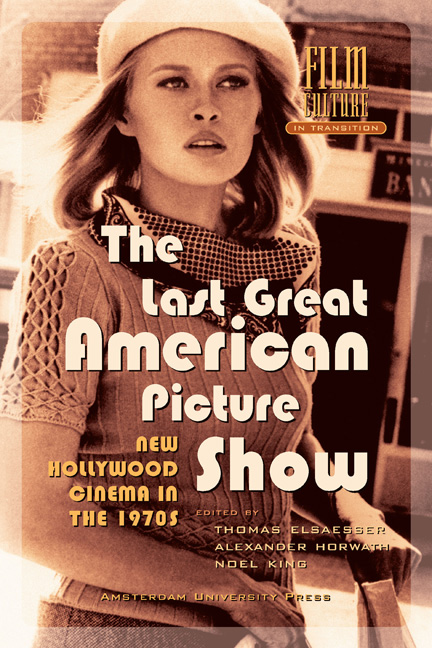

- The Last Great American Picture ShowNew Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s, pp. 37 - 70Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2004

- 3

- Cited by