Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

7 - Do we owe them just because they helped us?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

Summary

Kopano Lebelo grew up during apartheid in a township near Pretoria where, when he was still a teenager, he was drafted by the African National Congress (ANC) to recruit others in the struggle. Through his work with the ANC, he lived, studied and worked in various countries on the continent and in Europe, later studying for his master's degree in the United States. Since 2001, Lebelo has lived in suburban Pretoria with his teenage daughter, and is largely disengaged from formal political activism.

I regard myself as one of the lucky ones, exposed to fighting for liberation at an early age. It took away my childhood and my youth, which I didn't enjoy much, but the ANC moulded me and made me what I am today. I go back to the township now and I look at the people I grew up with and not even one can identify me as somebody that they know. All they think is, please can you buy me booze or give me a few bucks? I see myself through them and think, well, this is me if I hadn't gone out of the country.

There were six of us in our family. I have three older sisters and two younger brothers. After my parents passed on when I was very young, my uncle's family came to stay with us, so there were about 11 kids in that house in total. It was only when I came back from exile that I found out that the couple who raised me as their child – the only parents I knew – were in fact my uncle and aunt.

Growing up, my friends only saw life as it goes day by day, so when I started school I didn't see why I had to go. Not that I had much of a choice. But, at the age of 11, I started to go to the Zwartkop golf course, following some of the older kids who would go and get pocket money there as caddies. My parents didn't approve but I went anyway.

Later, I ran away and joined my friends, staying for about five months under Zwartkop Bridge between the R101 and Hans Strydom Drive, right next to the golf course.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

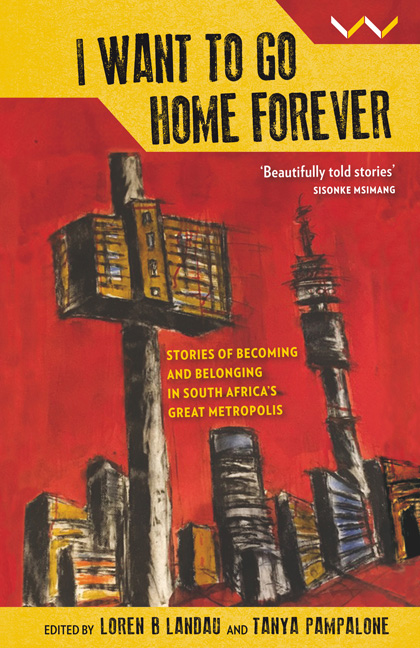

- I Want to Go Home ForeverStories of Becoming and Belonging in South Africa's Great Metropolis, pp. 96 - 107Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2018