Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- 18 Player Piano Roll

- 19 Champagne

- 20 Steamboat Willie

- 21 PH-Lamp

- 22 Climbing Rose

- 23 Penguin Paperback

- 24 Ferragamo Wedge

- 25 Aspirin Pill

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

25 - Aspirin Pill

from Modern Times

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- 18 Player Piano Roll

- 19 Champagne

- 20 Steamboat Willie

- 21 PH-Lamp

- 22 Climbing Rose

- 23 Penguin Paperback

- 24 Ferragamo Wedge

- 25 Aspirin Pill

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

Summary

ON 30 AUGUST 1915, parliamentarian William Kelly took to the floor of the Australian Federal House of Representatives, troubled by an issue that he felt was plaguing the Australian war effort: enemy-owned trademarks.

Kelly could not believe that his fellow countrymen were so willing to promote the property of the enemy, and was adamant that no product bearing such trademarks should be sold in Australian stores:

The point I want to make is, if during the war we kill a trade mark, we can kill the trade absolutely … If, by using the same trade mark, and by still requiring people to ask for the same things, they [the enemy owner] can keep the trade alive until after the war, they will have achieved their purpose. Take the case of aspirin … the public [has] been educated to ask for aspirin, and the enemy want to make the public ask for it until the war is over.

Kelly's statement highlights the power of registered trademarks in early 20thcentury consumer culture, and, more specifically, the power of Australian registered trademark 829, for the word ASPIRIN. Australia was not the only country that grappled with a reliance on German products and German-owned intellectual property during World War I. Many countries were caught on the horns of this dilemma, and, more often than not, aspirin was at the center of the struggle—as an object, as a product, as a recipient of multiple forms of intellectual property protection. How this object achieved global dominance, and how it continues to maintain a market presence today, is a story that spans multiple countries and centuries.

Like many legends, aspirin—the object, product, and name—has a mythical, disputed origin story. There is no dispute, however, as to the company it originated from: in 1863 Friedrich Bayer and Johann Friedrich Weskott established Friedrich Bayer & Company, entering the lucrative dye market dominating German industry in the mid-19th century. When Bayer and Weskott died—in 1880 and 1876 respectively— the company was taken over by Bayer's son-in-law, Carl Rumpff. Among a group of new employees appointed under Rumpff was Friedrich Carl Duisberg, commonly known as “Carl,” who was originally involved in dye manufacture but ultimately proposed the company's transition to chemical and medicinal research.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

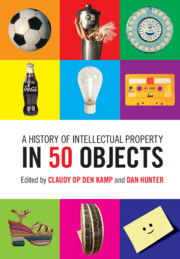

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 208 - 215Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019