XIII - Seminar from March 9, 1983

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 October 2023

Summary

Today we are going to wrap up our examination of problems posed by the birth and the first development of philosophy. And if, in this affair, I have taken Heraclitus as the nodal point, it’s because, all while completing in a sense a first cycle of philosophical elaboration, his oeuvre also contains the germs for all that would follow. I remind you that Heraclitus thrived in about 500 BC, and that in this era we already have seventy-five years of explicit philosophy, nearly three centuries of great poetry (Homer, Hesiod), and two centuries of lyric poetry, even if it’s in the sixth century that the latter became developed. And from the start lyric poetry, far from being a simple expression of affects or sentiments, also presents statements of philosophical and political reach. Such is the case with a celebrated passage of Archilochus (second half of the seventh century), which is absolutely surprising in this respect. There’s this career soldier, perhaps a mercenary, who one day fled the battlefield, leaving his shield behind—the most shameful act of cowardice in ancient Greece— and he writes, “I threw down shield; I can always buy another.” This is a frontal assault against the common belief about what virile virtues are, i.e. the bravery of the soldier. Moreover, we would find in lyric poetry, if we had time to pause here, more than an analogical statement implying a critique of the instituted beliefs and norms.

One of the results of this first unfolding, i.e. of the first three-quarters of a century of philosophy, is the separation in and by this movement between being and appearing, between what is and what gives itself to us qua human beings. This is a necessary result of the research in which the Ionians were already engaged when they wanted to find a principle, an archē, as Aristotle would say down the line in writing (or rewriting) this history, which is in effect allo ti para tauta, i.e. something else alongside what appears.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

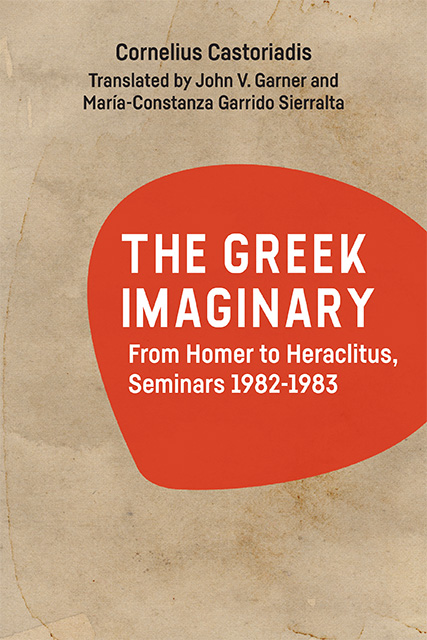

- The Greek ImaginaryFrom Homer to Heraclitus, Seminars 1982-1983, pp. 225 - 242Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2023