Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements and original sources

- Brief chronology

- Honours

- Introduction

- 1 A Quaker upbringing

- 2 How about studying insulin?

- 3 Radioactive sequencing of proteins and nucleic acids

- 4 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Early life

- 5 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Insulin and the Biochemistry Department, University of Cambridge

- 6 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Nucleic acids at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge

- 7 Post-Sanger sequencing: high-throughput automated sequencing

- 8 Cancer: the impact of new-generation sequencing

- 9 Commentaries on Fred Sanger’s scientific legacy

- Epilogue

- Appendix: Complete bibliography of Fred Sanger

- Notes

- Index

- Plates

5 - Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Insulin and the Biochemistry Department, University of Cambridge

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 November 2014

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements and original sources

- Brief chronology

- Honours

- Introduction

- 1 A Quaker upbringing

- 2 How about studying insulin?

- 3 Radioactive sequencing of proteins and nucleic acids

- 4 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Early life

- 5 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Insulin and the Biochemistry Department, University of Cambridge

- 6 Interview of Fred by the author in 1992: Nucleic acids at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge

- 7 Post-Sanger sequencing: high-throughput automated sequencing

- 8 Cancer: the impact of new-generation sequencing

- 9 Commentaries on Fred Sanger’s scientific legacy

- Epilogue

- Appendix: Complete bibliography of Fred Sanger

- Notes

- Index

- Plates

Summary

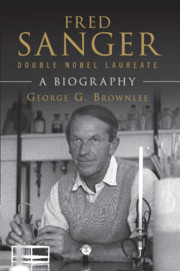

Fred Sanger (FS) and I (GB) are seated in a recording studio at Imperial College, London. This is a slightly edited transcript of the continuing interview.

Postgraduate research at Cambridge, 1940–1943

GBI’ve read, Fred, that at this stage you had still not quite decided to go into research.

FSWell, the thing is, I had not really decided that I was that good. I hadn’t been getting first classes in my Part I exams, and so I really didn’t have the confidence that I could do research. Usually you had to get a first to go into research. In this Part II Biochemistry there were all these brainy people who had got firsts in their Part I. They all seemed very clever compared to me. So at the end of the year I took the exams and I sort of went off and didn’t think too much about what I was going to do. In fact, I was thinking I would probably do some war work of some sort. War had broken out. But then, to my surprise, someone had seen in the paper that I had got a first. Actually, I was staying with my cousin. He was in the Air Force and he had been to the mess and he had just had a look at the Cambridge results in The Times and he’d seen I had got a first. And I said that’s ridiculous, it couldn’t be, but it was so. I had got a first. There were just two of us who had got firsts in this exam. So that changed my mind. So there was the possibility of doing research.

GBBut before you actually started research you had actually preplanned some training in Devon, I understand.

FSYes, that’s right, I went to a place called Spison (now Spiceland), a Quaker Relief Training Centre, which was a training place for conscientious objectors, where I was learning various things they could do to help save lives, instead of taking lives. We learned agriculture and a bit about building, and after I had done that course I went to work in a hospital, cleaning the floors and that sort of thing – just as an orderly. I started work there. That was the first job I had. I got 10 shillings (50p) a week for that.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Fred Sanger - Double Nobel LaureateA Biography, pp. 68 - 97Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014