Introduction: Rending and Reading the Flesh

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

SKIN is the parchment upon which identity is written. Class, race, ethnicity and gender are read upon the human surface. Removing skin tears away identity and leaves a blank slate upon which law, punishment, sanctity or monstrosity can be inscribed. Flaying strips away the means by which people see themselves or are viewed by others. Modern popular culture is fascinated with flaying – it often appears as a motif in horror films or serial crime dramas because, as Judith Halberstam writes, ‘[s]kin is at once the most fragile of boundaries and the most stable of signifiers; it is the site of entry for the vampire, the signifier of race for the nineteenthcentury monster’. In the 1991 film Silence of the Lambs, the serial killer branded ‘Buffalo Bill’ by the sensational media dresses up in a patchwork of skin sewn together to make a ‘woman suit’; prancing in front of a mirror, he becomes ‘a layered body, a body of many surfaces laid upon one another’. For ‘Bill’ flaying is part of the transformative act through which he can emerge from a chrysalis of conflicting identities into a fully formed entity. The voyeuristic act of watching ‘Bill’ watching himself ‘transformed’ horrifies and, at the same time, captivates. In this sense, skin becomes ‘a metaphor for surface, for the external; it is the place of pleasure and the site of pain; it is the thin sheet that masks bloody horror’. This metaphor of skin as a surface for touch, pain, pleasure, torment and suffering is not exclusively a modern phenomenon.

Frequently when flaying is employed in modern popular culture (though not in Silence of the Lambs) it evokes a sense of the medieval – or what is assumed to be medieval. Like torture, flaying is one of those acts that modern audiences generally prefer to locate in a distant past, the product of a less enlightened age. Thus, it is often – erroneously – enumerated as one of many ‘medieval’ horrors, and it is used in fantasy and popular culture to evoke a particularly ‘medieval’ kind of atrocity. In George R. R. Martin's wildly popular modern fantasy series Song of Ice and Fire, a flayed man acts as a sigil for one of the more brutal houses. The HBO film adaptation, Game of Thrones, treats modern viewers to the display of banners adorned with a stylistic image of a skinless corpse.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

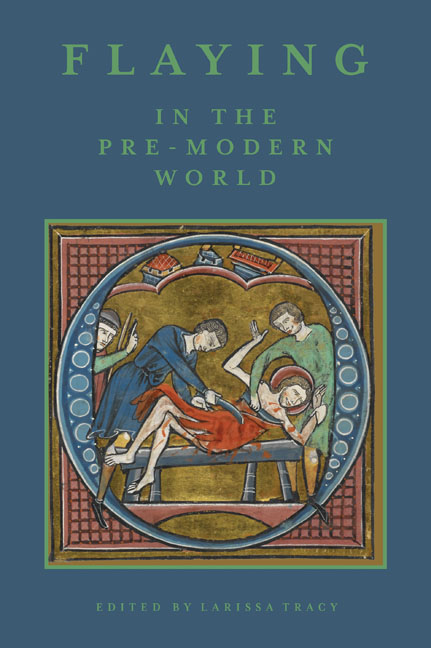

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 1 - 18Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017