Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Glossary

- List of Characters

- Prologue: On Our Watch

- Darfur and the Crime of Genocide

- Settlement Cluster Map of Darfur, Sudan

- 1 Darfur Crime Scenes

- 2 The Crime of Crimes

- 3 While Criminology Slept with Heather Schoenfeld

- 4 Flip-Flopping on Darfur with Alberto Palloni and Patricia Parker

- 5 Eyewitnessing Genocide

- 6 The Rolling Genocide

- 7 The Racial Spark

- 8 Global Shadows

- Epilogue: Collective R2P

- Appendix: Genocidal Statistics

- Notes

- Index

- Titles in the series

Epilogue: Collective R2P

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Glossary

- List of Characters

- Prologue: On Our Watch

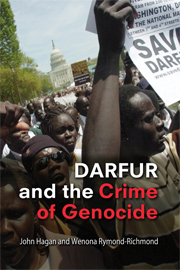

- Darfur and the Crime of Genocide

- Settlement Cluster Map of Darfur, Sudan

- 1 Darfur Crime Scenes

- 2 The Crime of Crimes

- 3 While Criminology Slept with Heather Schoenfeld

- 4 Flip-Flopping on Darfur with Alberto Palloni and Patricia Parker

- 5 Eyewitnessing Genocide

- 6 The Rolling Genocide

- 7 The Racial Spark

- 8 Global Shadows

- Epilogue: Collective R2P

- Appendix: Genocidal Statistics

- Notes

- Index

- Titles in the series

Summary

Imagine you wake up in the early hours of the morning and hear the screams of a woman from the street outside your window. What would you do? About a dozen bystanders saw or heard Kitty Genovese sexually assaulted and stabbed to death in 1964 in New York City, but did nothing. The story became a national symbol of the loss of community in urban America and spawned a research literature on “bystander effects” and the “willingness to intervene.” A body of jurisprudence evolved to support “Good Samaritan” laws encouraging help for fellow citizens in distress. The image of Kitty Genovese dying unaided on a New York City sidewalk haunted Americans.

For better or worse, idle bystanders are also members of communities. The criminologist Robert Sampson advanced our understanding of the collective propensities and capacities of communities to intervene by asking sampled respondents in Chicago neighborhoods in the 1990s about their willingness to watch out for the children of others and actively respond to neighborhood crimes. He found he could characterize whole neighborhoods in terms of their “collective efficacy” in monitoring and controlling crime victimization. The implication is that not just individuals vary in their willingness to intervene but that also neighborhoods, whole communities, entire societies, and even world bodies – such as the UN – are similarly enabled if not obliged.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Darfur and the Crime of Genocide , pp. 219 - 222Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2008