Book contents

- Frontmmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction

- Chapter Two The City in Context: An Historical Ambivalence

- Chapter Three City of Light: Paris as Spectacle

- Chapter Four City of Darkness: The Camera Goes Down the Streets: ‘The Hidden Spirit Under the Familiar Façade’

- Chapter Five Divided City: The Divided City in Context

- Chapter Six Conclusion

- Notes

- Appendices

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

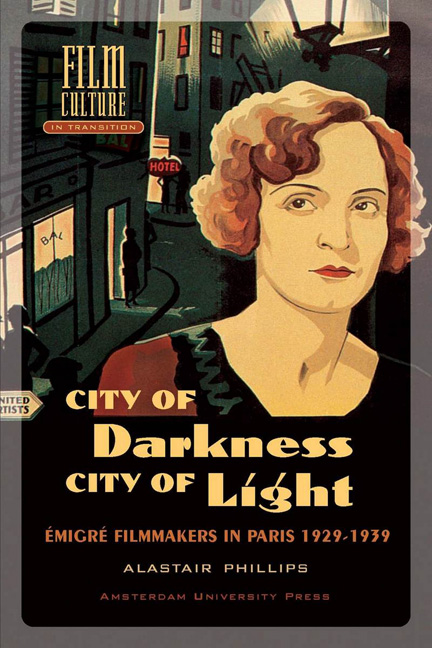

Chapter Four - City of Darkness: The Camera Goes Down the Streets: ‘The Hidden Spirit Under the Familiar Façade’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 January 2021

- Frontmmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction

- Chapter Two The City in Context: An Historical Ambivalence

- Chapter Three City of Light: Paris as Spectacle

- Chapter Four City of Darkness: The Camera Goes Down the Streets: ‘The Hidden Spirit Under the Familiar Façade’

- Chapter Five Divided City: The Divided City in Context

- Chapter Six Conclusion

- Notes

- Appendices

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

Summary

The Paris cinema auditorium of the 1930s was a place city dwellers largely entered at night, attracted by the building façade's display lights. Off the street, the audience found themselves in darkness again for the duration of the evening's main entertainment whilst images of the city were projected via light onto the screen. Discussing the work of the novelist Emile Zola in relation to the historical depiction of social experience in the French capital, Louis Chevalier wrote: ‘paradoxically (…) the triumph of light, for him, far from eradicated the shadow and the past which it concealed. It actually accorded it a new form of life as if light was a dazzling container for shadow’ (1980, 23). To unravel exactly what the legacy of this sense of urban “darkness” meant in relation to the émigrés’ interpretation of Paris, we first need to consider the depiction of the street and the emphasis on authenticity and social concern found in strains of French realist cinema of the period. In a key polemical article “Quand le cinéma descendra-t-il dans la rue?” (WhenWill the Cinema Go Down the Street?), published in Cinémagazine in November 1933, Marcel Carné anticipated the fascination that the streets of Paris would hold for filmmakers and filmgoers alike throughout the decade. Carné called Paris “the two-faced city”. By this he meant that according to established tropes of representation, Paris had been divided in terms of place and class between the frivolous high life and the “real world” of the ordinary urban dweller. Carné thought there had been too much of “the murky and inflated ambiance of night clubs, dancing couples, and a non-existent nobility” at the expense of “the simple life of humble people (…) the atmosphere of hard-working humanity” (in Abel 1993, 129). Since the development of Haussmanisation in the nineteenth century, “the simple life of humble people” had, to a large extent, become associated with darkness in the medical and socio-scientific writings of the day.Writers frequently stressed the association between the proliferation of disease and the darkness of the typical Parisian overcrowded faubourg. “Tuberculosis is the disease of darkness” the Commission d’Extension de Paris wrote in 1913, for example. “To combat it effectively, one must first of all oppose it with its natural enemy, the sun” (in Evenson 1979, 211).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- City of Darkness, City of LightÉmigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929–1939, pp. 107 - 148Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2003