Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Maps, Figures & Illustrations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Becoming Maasai: Introduction

- III Being Maasai: Introduction

- 7 Becoming Maasai, Being in Time

- 8 The World of Telelia: Reflections of a Maasai Woman in Matapato

- 9 'The Eye that Wants a Person, Where Can It Not See?': Inclusion, Exclusion, and Boundary Shifters in Maasai Identity

- 10 Aesthetics, Expertise, and Ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai Perspectives on Personal Ornament

- IV Contestations and Redefinitions: Introduction

- V Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

10 - Aesthetics, Expertise, and Ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai Perspectives on Personal Ornament

from III - Being Maasai: Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 August 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Maps, Figures & Illustrations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Becoming Maasai: Introduction

- III Being Maasai: Introduction

- 7 Becoming Maasai, Being in Time

- 8 The World of Telelia: Reflections of a Maasai Woman in Matapato

- 9 'The Eye that Wants a Person, Where Can It Not See?': Inclusion, Exclusion, and Boundary Shifters in Maasai Identity

- 10 Aesthetics, Expertise, and Ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai Perspectives on Personal Ornament

- IV Contestations and Redefinitions: Introduction

- V Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

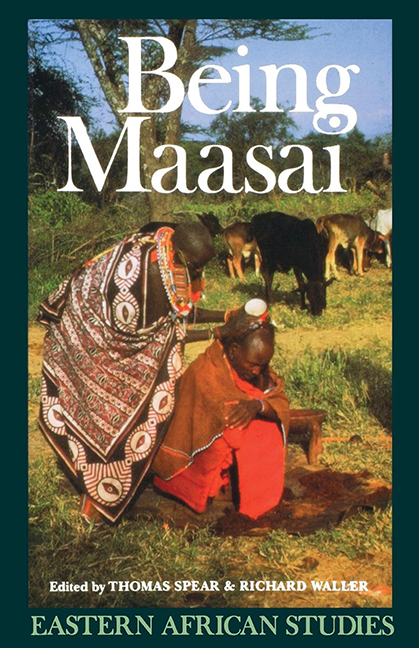

'If Kopot Edina gets dressed up with beads, you'd think she was Maasai.'

'Who [in the picture] is Kopot Edina?'

'This one.'

'You can't see clearly that this is Kopot Edina.'

'You'd think it's a young Maasai woman.'

This snatch of conversation comes from commentary made by Kaplelach and Kipchornwonek Okiek as they looked at pictures of themselves. Had a Maasai woman been present to view the pictures, her remarks might have been quite different. Instead, she might have picked out what she would regard as glaring errors and inconsistencies in the way the lovely young Okiot woman was dressed as she came out of seclusion after initiation.

The central purpose of this paper is to consider processes through which ethnic identity is claimed, advertised, and negotiated by looking closely at a key visual index of ethnicity in eastern Africa, beaded personal ornament. Personal ornament provides a prominent example of the way people can constitute a common ground of understanding and identity through a set of signs with general similarities of both form and function, and yet simultaneously differentiate among those who use the common signs. The distinctions they emphasize can be formal, functional, and/or evaluative.

The young Okiot woman in the picture, for instance, wears a necklace that a Maasai woman would see as incongruous because her understanding is that it is worn only on or after a woman's wedding day. Okiek wear the same ornament, but have a broader definition of when it is appropriate. Details of the young woman's ornaments show similar disjunctions between Okiek and Maasai understandings of acceptable aesthetic form, but only Maasai condemn them because the differences offend only their sensibilities. Maasai-like ornaments are recontextualized and redefined in Okiek practice, incorporated into Okiek understandings and evaluations. Yet they are similar enough to those of Maasai that they can also be perceived and evaluated through Maasai understandings. In that case, differences Okiek introduce are often regarded as flaws.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Being MaasaiEthnicity and Identity in East Africa, pp. 195 - 222Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 1993