Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: after the shock city

- 1 Citizenship and the Interwar City

- 2 Urban Utopias and Education

- 3 Celebrating the City

- 4 History, Progress and Community Performance

- 5 The Citizen of Tomorrow

- 6 Civic Culture and Welfare

- Conclusion: after the citizenship city

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - The Citizen of Tomorrow

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 September 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: after the shock city

- 1 Citizenship and the Interwar City

- 2 Urban Utopias and Education

- 3 Celebrating the City

- 4 History, Progress and Community Performance

- 5 The Citizen of Tomorrow

- 6 Civic Culture and Welfare

- Conclusion: after the citizenship city

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

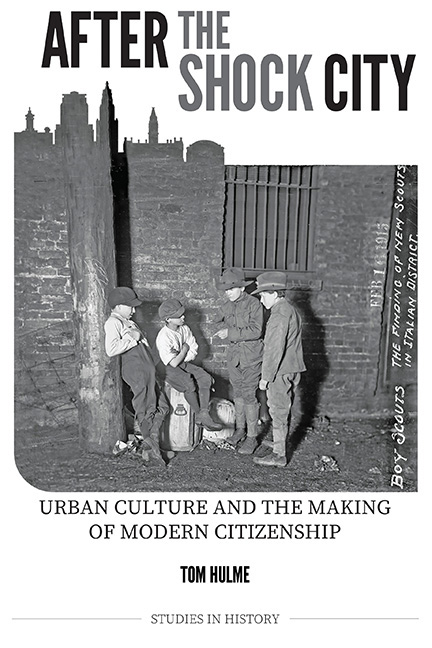

For many reformers and associations, the central question of citizenship was how society should guide the lives of the young. They were the next generation: the clay from which workers, soldiers and mothers of the nation would be sculpted. Youth citizenship was conceptualised, in many ways, as an urban problem that had a civic solution. Changing the city and its public culture, reformers believed, would transform both health and behaviour. Fears about the condition of city children were nothing new, and by the late Victorian years there was already an established network of voluntary and charitable organisations that endeavoured to provide direction, welfare and citizenship training. But the problem had evolved by the 1920s. Older debates about urban degeneration and ‘national efficiency’ were now combined with extensive sociological investigation and criticism of how modern youths spent their leisure time. A renewed sense of urgency emerged in the 1930s with the Great Depression, the rise of extreme political regimes in continental Europe and the looming prospect of another global war. Mass unemployment sparked contradictory fears: on the one hand, of possible revolutionary behaviour; and, on the other, of political apathy. Stopping youths from being seduced by crime, malaise or radical ideologies were all of paramount importance.

A new type of citizen, equipped for these competitive challenges, was shaped by the state and voluntary associations. Individual fitness was still emphasised – an element of continuity from the late nineteenth century. But there was also a shift towards foregrounding community and cohesion in the fragmented modern city, reflecting the importance of the ideals promoted by civics education and urban festivals. Youth citizens needed good personal health and morality, but also an enthusiasm for teamwork and social conformity under the umbrella of a collective civic identity. These attributes fitted them into future roles in the local and national economy, urban society and even possible warfare. Young people and their bodies, then, were the problem, but ‘youth’ was a catch-all term for a large group that had many differences in gender, class, race and ethnicity, as well as simply in terms of age. It could, following the growth of scientific and biological understandings of adolescence as a stage of life, be associated with the developmental phase of puberty – itself difficult to pin down in terms of an age range.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- After the Shock CityUrban Culture and the Making of Modern Citizenship, pp. 136 - 166Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019