Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- I The Busch Family

- II The Prodigy

- III The Cologne Conservatory

- IV The Young Virtuoso

- V The Vienna Years

- VI Berlin and Busoni

- VII The Darmstadt Days

- VIII Burgeoning in Basel

- IX The Break

- X Busch the Man

- XI The Chamber Players

- XII The Lucerne Festival

- Volume Two: 1939–52

- XIII The New World

- XIV Between Two Continents

- XV The Marlboro School of Music

- Appendices

- Envoi: Erik Chisholm talks about Adolf Busch

- Select Bibliography

- Index to Discography

- Index of Busch’s Compositions

- General Index

- Index to Adolf Busch’s Compositions on Record

- Index to Discography

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- I The Busch Family

- II The Prodigy

- III The Cologne Conservatory

- IV The Young Virtuoso

- V The Vienna Years

- VI Berlin and Busoni

- VII The Darmstadt Days

- VIII Burgeoning in Basel

- IX The Break

- X Busch the Man

- XI The Chamber Players

- XII The Lucerne Festival

- Volume Two: 1939–52

- XIII The New World

- XIV Between Two Continents

- XV The Marlboro School of Music

- Appendices

- Envoi: Erik Chisholm talks about Adolf Busch

- Select Bibliography

- Index to Discography

- Index of Busch’s Compositions

- General Index

- Index to Adolf Busch’s Compositions on Record

- Index to Discography

Summary

This crisis in his life – when he cut himself off from the landscape that had formed him and the tradition that was his main source of cultural nourishment – is perhaps the best point at which to consider Adolf Busch the man, through the perceptions of relations and friends. Like his brother Fritz, he was deceptively tall, a little under six foot (1.79 metres): his heavy build in adulthood made him appear stockier and his skiing accident left him with one leg slightly shorter than the other and an almost imperceptible limp. ‘He had a peasant figure – he wasn't slim and he wasn't fat’, his niece Hildegart Nicholas said. As Evelyn Rothwell saw him, ‘He was like a large, benign bear, slightly shaggy, always with his hair falling over his face – a round, highly coloured face and bright, piercing blue eyes. He was always warm, outgoing, interested, eager – almost like a child’. This view was echoed by Dea Gombrich: ‘It was almost a child's face’. Meeting him with his son-in-law in 1939, a journalist reported that ‘his unlined, pink face and athletic figure make him look almost as young as the slight, boyish Serkin’. In Toni Booth's eyes ‘He was tall, with very broad shoulders, and looked as if he liked running’. And Amalie Serkin saw him as ‘not at all clumsy in appearance but stately, though never pompous – just a tall, big, blond man’. As a boy he had fair hair but it had darkened to reddish-brown by his early twenties – although in his fifties he still struck the young Eugene Istomin as ‘a great blond giant’. In the late 1920s and early 1930s he sported such a short crewcut that on his second visit to America he was described as ‘bristly haired’. Robert Dressler, Busch's pupil in his last years, said: ‘To me he always looked perfectly healthy, hale and hearty. He had very red cheeks, which is typical of a certain type of mostly southern German’. Conte Enrico di San Martino, president of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, wrote:

Busch is an artist who certainly deserves a special mention. His external appearance clearly does not correspond with the old, romanticised image of the slightly gaunt, pale, excitable, agitated artist with untidy long hair.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

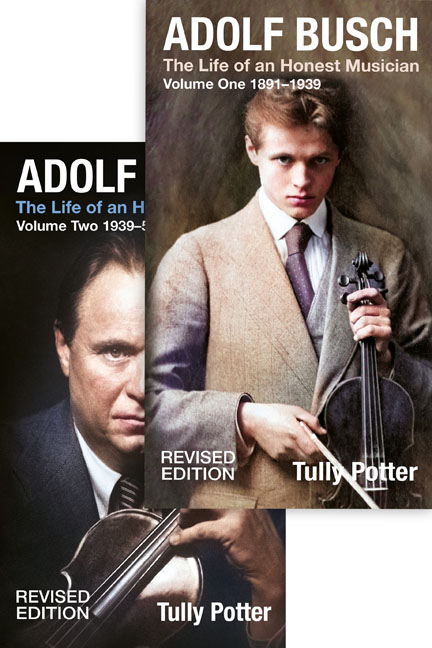

- Adolf BuschThe Life of an Honest Musician, pp. 567 - 592Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2024