Introduction

Mental disorders are associated with higher mortality rates, being accountable for approximately 8 million (or 14%) of all annual deaths worldwide (Walker, McGee, & Druss, Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015). Mortality prevention strategies in psychiatry require disorder and cause-specific mortality data for optimal resource allocation. In the last decade, large epidemiological studies have addressed this issue (Plana-Ripoll et al., Reference Plana-Ripoll, Pedersen, Agerbo, Holtz, Erlangsen, Canudas-Romo and Laursen2019; Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015; Weye et al., Reference Weye, Momen, Christensen, Iburg, Dalsgaard, Laursen and Plana-Ripoll2020). They consistently showed that all major mental disorders lead to excess mortality, with risk increments varying across conditions. For instance, in a Danish populational study published in 2019, mortality rates associated with mental disorders were increased from two to four-fold (in mood and substance use disorders, respectively) (Plana-Ripoll et al., Reference Plana-Ripoll, Pedersen, Agerbo, Holtz, Erlangsen, Canudas-Romo and Laursen2019). This and other studies also showed that while people with mental disorders face an increase in multiple causes of mortality, the majority of deaths in this population is caused by potentially treatable physical illnesses (Erlangsen et al., Reference Erlangsen, Andersen, Toender, Laursen, Nordentoft and Canudas-Romo2017; Jayatilleke et al., Reference Jayatilleke, Hayes, Dutta, Shetty, Hotopf, Chang and Stewart2017).

According to a recent meta-analysis, most studies on psychiatric mortality used information obtained by linkage with administrative healthcare databases (Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015). This type of data source often has large samples and long follow-up periods, enabling precise risk estimates. But despite its potential robustness, registry-based studies have important limitations, such as data completeness and correctness issues; case identification restricted to those with a previous formal diagnosis; lack of diagnostic validation; and overestimated risk estimates due to a high proportion of severe or inpatient cases (Jayatilleke et al., Reference Jayatilleke, Hayes, Dutta, Shetty, Hotopf, Chang and Stewart2017; Krumholz, Reference Krumholz2009; Weye et al., Reference Weye, Momen, Christensen, Iburg, Dalsgaard, Laursen and Plana-Ripoll2020). Alternative methods to address these limitations include the use of diagnostic questionnaires to detect mental disorders.

One of the few large cohorts using psychiatric diagnostic questionnaires is the UK Biobank. The UK Biobank is a prospective study of over half a million middle-aged UK participants recruited in 2006–2010 (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh and Collins2015). Its objective is ‘to improve our understanding of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a wide range of serious and life-threatening illnesses,’ among them mental disorders (UK Biobank, 2021a). For that, it relies on different data sources such as questionnaires, computer-guided interviews, and linkage with records from the UK National Health Service. These sources allow for prolonged and detailed morbidity and mortality follow-up (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007).

Initially, the UK Biobank identified mental disorders mainly by questions on mood symptoms and self-report of medical conditions at baseline. It also captured episodes of psychiatric illnesses using hospital data linkage. In 2016, recognizing the importance of more detailed psychiatric phenotyping, the UK Biobank team implemented a self-completed online Mental Health Questionnaire. Developed by an expert steering group, this tool captures lifetime and current/recent symptoms of common mental disorders using a set of standard validated questionnaires. Its primary focus is symptom-based identification of disorders that bring a greater burden to the cohort, including depression and anxiety. Covering a spectrum of illness severities, the questionnaire identifies more cases than other mental disorder indicators in the UK Biobank (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019). To date, it has been completed by around 160 000 participants. The UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire data is an unparalleled resource, which can be combined with other indicators of mental disorders in the UK Biobank to assess their impact on mortality (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2017).

This study uses data from the UK Biobank to analyze mortality, survival, and causes of death associated with mental disorders. Our aims were to: (1) study the mortality associated with a wide selection of mental disorders in a large middle-aged cohort and (2) contrast results obtained when disorders are identified by symptom-based outcomes derived from the Mental Health Questionnaire v. hospital data linkage of International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnoses. It was our hypothesis that most mental disorders would be associated with increased mortality risk, regardless of the identification method. We also hypothesized that disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes would be associated with lower mortality risk and with a distinct pattern of causes of death v. disorders identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses.

Method

Study design

This is a longitudinal cohort study using data from the UK Biobank to estimate mortality rates, survival, and proportions of deaths by cause in individuals identified with mental disorders. Our study is described per the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (von Elm et al., Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2008).

Setting

The UK Biobank coordinating center is based at the Manchester University in Manchester, England. Study planning and design started in 1999 and recruitment in 2006 (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007). Baseline data were collected in 2006–2010 in 22 assessment centers across England, Scotland, and Wales (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh and Collins2015). Assessment centers were academic clinical research facilities or serviced offices adapted to host the data collection processes (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007). UK Biobank participants will be followed up for at least 30 years (Ollier, Sprosen, & Peakman, Reference Ollier, Sprosen and Peakman2005).

Ethics

The UK Biobank has approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0382), with the Mental Health Questionnaire as an amendment (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020; UK Biobank, 2020). Its funding comes primarily from the Wellcome charity and the Medical Research Council (UK Biobank, n.d.-c). Anonymized study data are ‘available to bona fide researchers for health-related research in the public interest’ upon application (UK Biobank, 2021d). All UK Biobank participants signed a consent form before any study protocol implementation. Study participation was voluntary and did not involve compensation (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007).

Data collection

Data collection for the UK Biobank comprised of: (1) an in-person baseline assessment (to be repeated periodically in a cohort subset), consisting of an extensive self-completed touch-screen questionnaire, a computer-assisted interview, physical and functional measures, and biosample collection; (2) periodic linkage with healthcare and mortality data routinely collected by the UK National Health Service (NHS) (UK Biobank, n.d.-a; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007); and (3) various additional post-baseline assessments in cohort subsets to better characterize selected exposures and outcomes (including the Mental Health Questionnaire) (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019; UK Biobank, n.d.-a).

Mental Health Questionnaire

The UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire is composed of the following domains: (A) screening questions (self-reported mental disorder diagnoses); (B.1) current depression; (B.2) lifetime depression; (B.3) lifetime manic symptoms; (C.1) current anxiety disorder; (C.2) lifetime anxiety disorder; (D) addictions; (E.1) alcohol use; (E.2) cannabis use; (F) psychotic experience; (G.1) adverse events in childhood; (G.2) adverse events in adult life; (G.3) posttraumatic stress disorder; (H) self-harm and suicidal thoughts; (J) subjective well-being; and (K) free-text box. Most domains capture lifetime or current/recent psychiatric symptoms (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2017).

The questionnaire was designed by an expert group advised by a patient group. Sub-questionnaires composing each domain were selected based on content, length, psychometric properties, patient acceptability, and compatibility with international studies. Pre-existing validated assessments were used whenever possible. Otherwise, questions were written or adapted by the expert group (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020, Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2017).

Several domains of the questionnaire were based on the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF), modified to provide lifetime history (Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, Reference Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun and Wittchen1998; Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Potash, Mostafavi, Battle, Zhu and Weissman2017; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2017). The CIDI is a widely used instrument for mental health surveys created using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV). The CIDI-SF showed good accuracy when validated in a North American sample, but might overestimate diagnostic rates (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun and Wittchen1998; Sunderland, Andrews, Slade, & Peters, Reference Sunderland, Andrews, Slade and Peters2011).

Questionnaire responses can be used to derive symptom-based outcomes. Most of these outcomes are analogous to a mental disorder (for instance, depression or generalized anxiety disorder). Others represent syndromes that can occur in various disorders (such as ‘psychotic experience,’ which corresponds to potential psychotic symptoms). For brevity, we refer to all symptom-based outcomes as disorders. Participants meeting criteria for a symptom-based outcome are said to ‘likely’ have the corresponding mental disorder. Diagnostic confirmations would require clinical evaluations by trained professionals, which were not performed in the UK Biobank (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019, Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020).

Healthcare linkage data

As mentioned, the UK Biobank obtains ongoing data from linkage with the NHS, including hospital inpatient and death records. This information is collected separately from the NHS England, the NHS Scotland, and the NHS Wales, and released periodically by the UK Biobank. Our study used ICD-10 coded hospital inpatient diagnoses from each country, most of which are available starting in 1997, 1996, and 1999, respectively. We also used death records from 2006 to 30 September 2021 (censoring date) (UK Biobank, n.d.-b, 2019).

Sample size

The UK Biobank sample size was determined through simulation-based power calculations (described in detail in the study protocol) (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007). Each simulation considered assumptions about exposure prevalence and potential follow-up losses, as well as financial and logistical concerns. In summary, the simulations showed that 500 000 participants would generate a sufficient number of cases to estimate the effect of genetic and environmental exposures on several diseases of public health relevance. For instance, after 10 years of follow-up, 500 000 participants would generate at least 5000 incident cases of diseases such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and breast cancer. Considering an exposure with 10% of prevalence, 5000 cases would reliably detect odds ratios of the order of 1.5 in nested case–control studies.

Participants

Individuals included in the UK Biobank aged between 40 and 69 years at baseline and lived within approximately 25 miles (40 km) of one of the assessment centers (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Littlejohns, Sudlow, Doherty, Adamska, Sprosen and Allen2017; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007). Recruitment was performed by mail using contact information obtained from the NHS (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh and Collins2015; UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2007). Over 9 million invitations were sent, with an acceptance rate of around 5% (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Littlejohns, Sudlow, Doherty, Adamska, Sprosen and Allen2017).

The main dataset used in our study includes data from a total of 502 459 UK Biobank participants (data released in September 2020 under application number 30140 – the exact number of participants varies slightly over time due to consent withdrawals). Approximately 89% of them were recruited in England, 7% in Scotland, and 4% in Wales; their ethnicity was predominately white (95%) (UK Biobank, 2019). The median participant age at baseline was 58 years (interquartile range = 50–63), with a roughly balanced proportion of men and women (46% and 54%, respectively) (UK Biobank, 2021b). Despite its size, the UK Biobank sample is not considered populationally representative. Compared with the general UK population, UK Biobank participants were more likely to be older and female. In addition, they had better socioeconomic status and a lower prevalence of smoking and self-reported chronic illnesses (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Littlejohns, Sudlow, Doherty, Adamska, Sprosen and Allen2017).

The Mental Health Questionnaire has been available to all UK Biobank participants on an online platform since 2016 (UK Biobank, 2021c). Email invitations were sent to all participants who had agreed to email contact (approximately 67% of the cohort) (UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2017). To date, 157 331 participants (31% of the cohort) have fully completed the questionnaire, requiring a median time of 14 min. At baseline, questionnaire completers were younger and had better socioeconomic and health status than the whole UK Biobank sample. They also had a lower frequency of self-reported depressive symptoms (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020).

We excluded from our dataset 37 participants who were lost to follow-up and had their death reported by a family member, as the accuracy of this information and their exact date of death could not be determined. Two additional participants were excluded from the analyses using symptom-based outcomes because their date of completing the Mental Health Questionnaire was registered as posterior to their date of death.

Exposures and outcomes

Table 1 describes the indicators of mental disorders from the UK Biobank used in our study. These indicators were analyzed as binary exposures. Our primary exposures were symptom-based outcomes derived from the Mental Health Questionnaire, following the case definitions suggested by Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020), with non-cases as controls. Our outcome of interest in these analyses was time from completing the questionnaire to death (all-cause).

Table 1. Indicators of mental disorders in the UK Biobank used in this study

CIDI-SF, Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form, lifetime version; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-question version; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire 7-item scale; PCL-6, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian Short Version; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision.

a The UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire has other domains that were not included in our analyses (for instance, self-reported psychiatric diagnoses and questions on environmental exposures).

b We chose a cut-off of 10 instead of the usual eight points to increase specificity, as suggested by the World Health Organization (Babor et al., Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro2001).

c Main or secondary diagnoses recorded before the baseline data collection.

Secondarily, we used the following exposures obtained using hospital data linkage: (A) selected ICD-10 diagnoses or groups of diagnoses that best corresponded to each symptom-based outcome (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019), and (B) all ICD-10 diagnoses within Chapter 5 – ‘Mental and Behavioral Disorders’ grouped by section (block) (World Health Organization, 1992). We only considered diagnoses registered before the baseline data collection. Our outcome in these instances was time from baseline to death (all-cause).

Our analyses were adjusted by age. We also performed sensitivity analyses with additional adjustment by sex. For mental disorders identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses, we performed sensitivity analyses including only participants who completed the Mental Health Questionnaire. These latter analyses included diagnoses registered before the questionnaire completion and had time from completing the questionnaire to death (all-cause) as the outcome variable.

Statistical methods

Our analyses were performed in Python using the packages pandas, NumPy, statsmodels, causallib, lifelines, Matplotlib, seaborn, and rpy2, and in R using the package tableone. Some of our code snippets were adapted from R code written by Coleman and Davis (Reference Coleman and Davis2019).

We started our analyses by evaluating distributions and frequencies for each numeric and categorical variable. Model assumptions were checked with diagnostic plots and statistical tests. We assumed a significance level of 0.05 for all analyses. The p values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

For each exposure, we (1) described sociodemographic characteristics and mortality risk factors at baseline [selected based on previous literature (Ganna & Ingelsson, Reference Ganna and Ingelsson2015)], including medians and interquartile ranges for numeric variables and proportions for categorical variables; (2) calculated the number and percentage of participants who died; (3) calculated crude and age- (or age- and sex-) standardized mortality rates per 1000 persons-year. Standardization was performed using the direct method, with the whole sample under consideration as reference and categorizing age in 5-year intervals; (4) ran an age-adjusted Cox proportional hazards survival model with robust standard errors to assess its association with increased mortality risk. Results were reported as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals and adjusted p values from Wald tests. If the model required additional adjustment by sex, this was done by stratification; (5) calculated the proportion of participants dying from primary causes within each ICD-10 chapter (excluding deaths with no recorded cause). Our sensitivity analyses followed steps 2 to 4.

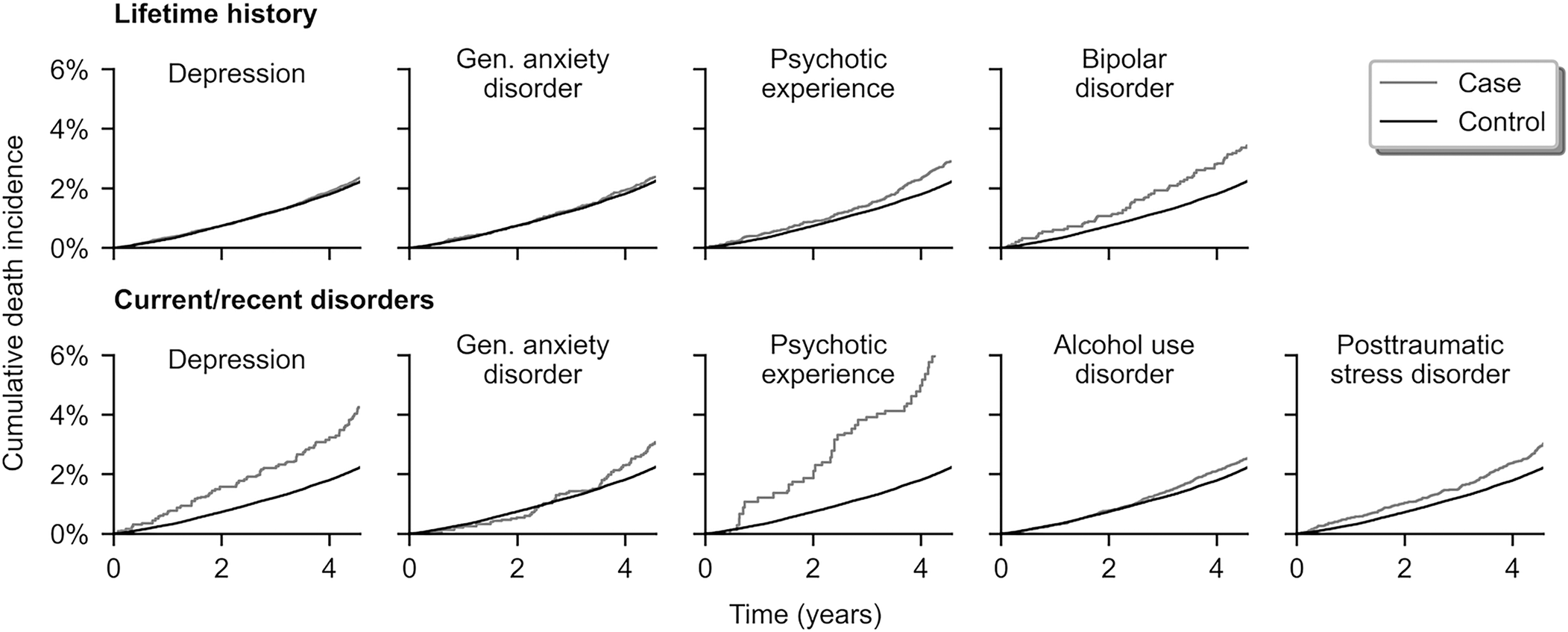

For mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes, we plotted the cumulative death incidence over time using Kaplan–Meier estimates (calculated as one minus the survival function and age-adjusted by inverse probability weights) (Xie & Liu, Reference Xie and Liu2005). We also ran and plotted two additional age-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models: the first using all conditions identified by symptom-based outcomes as covariates (to assess their independent association with survival), and the second with the number of conditions identified by symptom-based outcomes as covariates.

Results

Considering symptom-based outcomes, we analyzed data from 157 329 Mental Health Questionnaire completers. A total of 59 902 of them (38%) met criteria for at least one lifetime or current/recent mental disorder. Of these, approximately 65% met criteria for one disorder only; 21% for two; 8% for three; 3% for four; and 3% for five or more. The mental disorders most frequently identified were lifetime depression (24%), current alcohol use disorder (12%), and lifetime generalized anxiety disorder (7%). Sociodemographic characteristics and mortality risk factors varied in questionnaire completers identified with different mental disorders (online Supplementary Table S1A). Women were the majority across all disorders, except current alcohol use disorder (36%). Compared with lifetime disorders, current/recent disorders were generally associated with younger age, higher social deprivation (UK Biobank, 2018), lower income, and more frequent smoking and previous stroke.

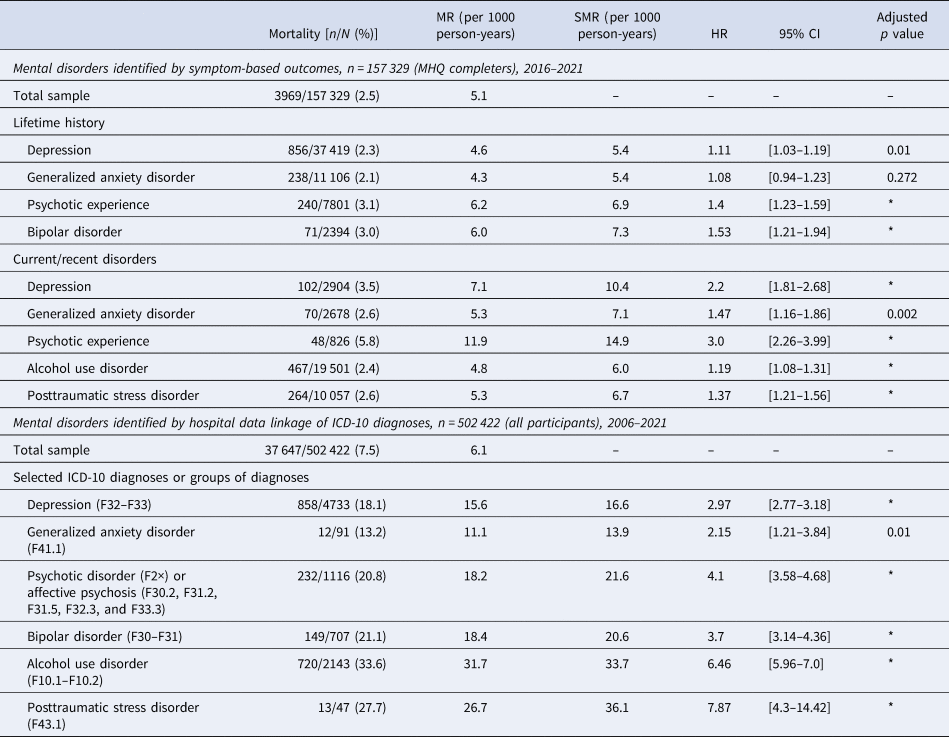

We found a significantly higher mortality risk in questionnaire completers meeting symptom-based criteria for lifetime or current depression, current generalized anxiety disorder, lifetime or recent psychotic experience, lifetime bipolar disorder, current alcohol use disorder, and current posttraumatic stress disorder (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was not significantly associated with increased mortality risk. Across all mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes, hazard ratios ranged from 1.08 to 3.0. The highest hazard ratios were observed among questionnaire completers identified with recent psychotic experience [HR = 3.0, 95% IC (2.26–3.99)], current depression [2.2 (1.81–2.68)], and lifetime bipolar disorder [1.53 (1.21–1.94)]. Recent psychotic experience, current depression, and current alcohol use disorder were significantly associated with increased mortality risk independently of other conditions (online Supplementary Fig. S1). We also found that the mortality risk increased consistently with the number of conditions identified by symptom-based outcomes (online Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 1. Age-adjusted cumulative death incidence associated with mental disorders in the UK Biobank. Mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes, n = 157 329 (Mental Health Questionnaire completers), 2016–2021.

Table 2. Age-adjusted mortality rates and hazard ratios associated with mental disorders in the UK Biobank

MHQ, Mental Health Questionnaire; MR, mortality rate; SMR, standardized mortality rate; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision.

*Adjusted p value <0.001.

Continues in online Supplementary Table S2A.

When looking at mental disorders identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses, we analyzed data from 502 422 UK Biobank participants (online Supplementary Tables 1B and 1C). Prevalence rates for all disorders or groups of disorders were 1% or lower. Overall, mental disorders identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses were associated with worse socioeconomic status and with a higher frequency of mortality risk factors than those identified by symptom-based outcomes.

All selected ICD-10 diagnoses or groups of diagnoses corresponding to symptom-based outcomes were significantly associated with increased mortality risk, with hazard ratios from 2.15 to 7.87 (Table 2). The highest hazard ratios were associated with posttraumatic stress disorder [7.87 (4.3–14.42)], alcohol use disorder [6.46 (5.96–7.0)], and psychotic disorder or affective psychosis [4.1 (3.58–4.68)]. Furthermore, all ICD-10 sections on mental and behavioral disorders were significantly associated with increased mortality risk, with hazard ratios from 2.02 to 5.44. The highest hazard ratios were associated with mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use [5.44 (5.11–5.78)], disorders of psychological development [4.99 (3.46–7.2)], and disorders of adult personality and behavior [4.6 (3.54–5.98)] (online Supplementary Table S2A).

Results of our age- and sex-adjusted sensitivity analyses were generally consistent with those described above (online Supplementary Table S2B). In these analyses, the only exposures not significantly associated with increased mortality risk were lifetime generalized anxiety disorder and current alcohol use disorder (symptom-based outcomes). In our sensitivity analyses based on hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses restricted to questionnaire completers, we observed a trend toward lower hazard ratios. However, many estimates in these analyses were imprecise and underpowered due to models with a small number of events (online Supplementary Table S2C) (Vittinghoff & McCulloch, Reference Vittinghoff and McCulloch2007).

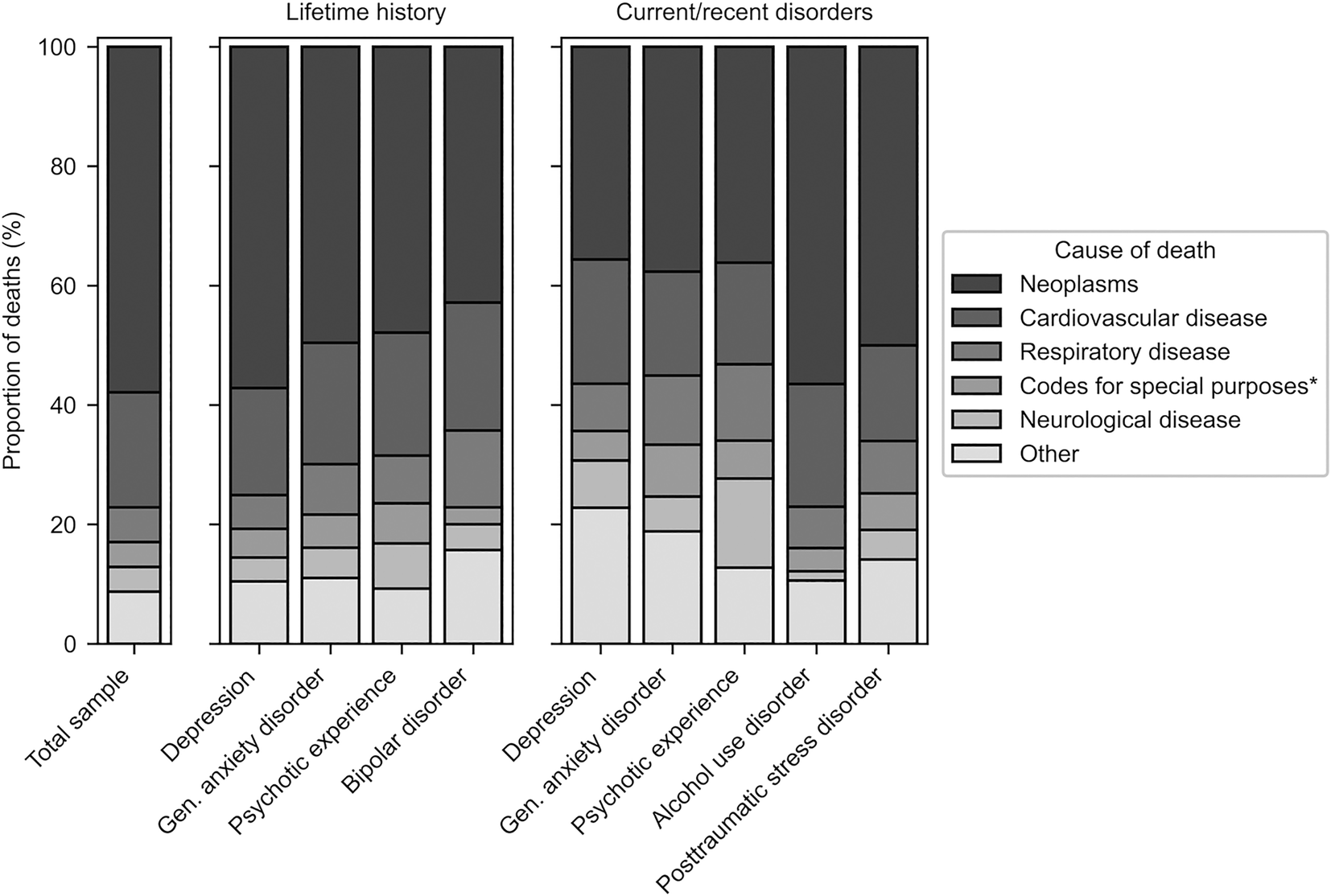

Figure 2 and online Supplementary Tables S3A to 3C show the proportion of deaths by cause (grouped by ICD-10 chapter) across mental disorders in the UK Biobank. Overall, neoplasms were the most common leading cause of death. However, mental disorders were generally associated with an increased proportion of deaths due to other causes, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Besides, deaths due to neoplasms were numerically surpassed by cardiovascular deaths in several conditions identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses. Mental disorders were also generally associated with an increased proportion of deaths from external (unnatural) causes, despite these being relatively infrequent. Another interesting finding is that ‘Codes for special purposes’ [which includes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)] was among the ICD-10 chapters most frequently contributing to deaths in our study.

Fig. 2. Proportion of deaths by cause (grouped by ICD-10 chapter) associated with mental disorders in the UK Biobank. Mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes, n = 157 329 (Mental Health Questionnaire completers), 2016–2021. ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. *Includes COVID-19 (ICD-10 U07.1–U07.2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to use data from the UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire to evaluate the association between mental disorders and mortality. Using symptom-based outcomes derived from the questionnaire, we found a significantly increased mortality risk among participants meeting criteria for lifetime depression, lifetime psychotic experience, lifetime bipolar disorder, and all current/recent disorders (depression, generalized anxiety disorder, psychotic experience, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder). Using hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses, we found a significantly increased mortality risk associated with all selected diagnoses or groups of diagnoses corresponding to symptom-based outcomes, as well as with all psychiatric diagnoses grouped by ICD-10 section. Mental disorders were associated with a predominance of natural deaths (mainly due to neoplasms and cardiovascular disease) but also with an increased proportion of unnatural deaths.

As expected, the results of our survival analyses varied when we identified mental disorders using symptom-based outcomes v. hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses. This occurred because each indicator selected different subgroups of UK Biobank participants as cases. As previously discussed, there are several advantages in identifying disorders using symptom-based outcomes derived from the Mental Health Questionnaire. Yet, the questionnaire is not equivalent to a gold-standard psychiatric interview (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen and Hotopf2020, Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019; Davis & Hotopf, Reference Davis and Hotopf2019). Also, it covers a limited number of disorders and might underidentify individuals with more severe cases, who may be unable to complete an online questionnaire. On the other hand, disorder identification using hospital data linkage covers all ICD-10 diagnostic codes and seems to have higher specificity for severe cases. However, this method lacks validation and detects a fraction of cases identified by symptom-based outcomes (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019). Taking these issues into account, our and other studies based on the UK Biobank data have used a combination of mental disorder indicators (Fabbri et al., Reference Fabbri, Hagenaars, John, Williams, Shrine, Moles and Lewis2021; Glanville et al., Reference Glanville, Coleman, Howard, Pain, Hanscombe, Jermy and Lewis2021a; Glanville, Coleman, O'Reilly, Galloway, & Lewis, Reference Glanville, Coleman, O'Reilly, Galloway and Lewis2021b; Ronaldson et al., Reference Ronaldson, Arias de la Torre, Gaughran, Bakolis, Hatch, Hotopf and & Dregan2020). This approach can generate risk estimates for a wide range of disorders and that are generalizable for different settings.

We found that depression, psychotic experience/disorder, and bipolar disorder were consistently associated with increased mortality risk (considering symptom-based outcomes or hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses as well as lifetime or current/recent assessment). Risk estimates were lower for disorders identified by lifetime symptom-based outcomes v. hospital data linkage (which, similarly, identify participants who ever received a diagnosis). For instance, the increase in mortality risk associated with lifetime bipolar disorder was 53% and 270% when based on symptom-based outcomes v. hospital data linkage (ICD-10 F30–F31), respectively. Beyond that, lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was only associated with increased mortality when identified by hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses. These findings reinforce the idea that this indicator tends to select more severe cases.

In our analyses using mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes, we found that all current/recent mental disorders were associated with increased mortality risk. Also, current/recent disorders were associated with higher risk estimates v. the corresponding lifetime disorders. These findings might indicate a less reliable identification of lifetime disorders due to recall bias (Patten et al., Reference Patten, Williams, Lavorato, Bulloch, D'Arcy and Streiner2012; Takayanagi et al., Reference Takayanagi, Spira, Roth, Gallo, Eaton and Mojtabai2014). In support of this idea, lifetime prevalence rates for mental disorders are halved when based on retrospective v. prospective assessments in a singular cohort (Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010). Another possible explanation for our findings is that the mortality risk associated with mental disorders is higher in the period close to their onset. Data from individuals with lifetime disorders who survived this initial period could then generate underestimations of the lifetime risk (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Hersen and Last1987).

Our findings add to the extensive literature showing that mental disorders can lead to several-fold increases in mortality risk. Although this phenomenon has been described for more than a century, its causal mechanisms are not fully elucidated (Jarvis, Reference Jarvis1850). Mental disorders seem to contribute to mortality through multiple individual and environmental factors, each perhaps having a modest contribution (Correll et al., Reference Correll, Solmi, Veronese, Bortolato, Rosson, Santonastaso and Stubbs2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Daumit, Dua, Aquila, Charlson, Cuijpers and Saxena2017). These factors include higher rates of chronic physical illnesses among people with mental disorders, combined with an increased vulnerability to death by external causes and worse access to care (Fridell et al., Reference Fridell, Bäckström, Hesse, Krantz, Perrin and Nyhlén2019; Too et al., Reference Too, Spittal, Bugeja, Reifels, Butterworth and Pirkis2019). Beyond that, mental disorders and mortality have common risk factors, such as genetic variants and early-life factors. This multicausal model is supported by our study, as it associates mental disorders with heterogeneous patterns of causes of death (Erlangsen et al., Reference Erlangsen, Andersen, Toender, Laursen, Nordentoft and Canudas-Romo2017; Jayatilleke et al., Reference Jayatilleke, Hayes, Dutta, Shetty, Hotopf, Chang and Stewart2017).

Ultimately, our study reinforces that most people with mental disorders die from natural causes. It also indicates that they die disproportionately more from largely preventable causes, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Premature natural deaths in this population are expected to decrease with effective prevention and management of physical illnesses (World Health Organization, 2018). People with mental disorders also face a higher risk of unnatural deaths such as suicides. Efforts to prevent these unnatural deaths involve identifying and providing evidence-based interventions to high-risk subgroups (Brodsky, Spruch-Feiner, & Stanley, Reference Brodsky, Spruch-Feiner and Stanley2018; Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015). A recent expert panel recognized the need for multiple interventions in reducing the mortality gap associated with mental disorders. It also advocated that these interventions be part of multilevel frameworks providing integrated mental and physical healthcare (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Daumit, Dua, Aquila, Charlson, Cuijpers and Saxena2017).

As we analyzed deaths occurring up to September 2021, our results were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020–2021, COVID-10 was the leading individual primary cause of death in the UK Biobank, accounting for around 15% of all deaths. COVID-19 was also one of the leading causes of death considering all deaths since the beginning of the cohort (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Bodinier, Whitaker, Delpierre, Vermeulen, Tzoulaki and Chadeau-Hyam2021; UK Biobank, 2021e). This is reflected in the important contribution of the ICD-10 chapter ‘Codes for special purposes’ (which includes COVID-19) to deaths in our study. The relationship between mental disorders and COVID-19 mortality has started to be investigated recently, with worrisome findings (Das-Munshi et al., Reference Das-Munshi, Chang, Bakolis, Broadbent, Dregan, Hotopf and Stewart2021; Nemani et al., Reference Nemani, Li, Olfson, Blessing, Razavian, Chen and Goff2021). In a study based on the UK Biobank data, mental disorders were associated with a doubled risk of death by COVID-19 (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Chen, Hu, Chen, Zeng, Sun and Song2020). Thus, the pandemic seems to have reproduced and perhaps amplified longstanding mortality inequalities in mental disorders.

Findings from our study should be interpreted in light of the limitations of the UK Biobank. The UK Biobank sample comprises middle-aged individuals who are mostly from White British backgrounds. Thus, our results should be generalizable only for similar populations. Another threat to the generalizability of our findings is potential selection bias in the UK Biobank, as its sample is not populationally representative. As mentioned, UK Biobank participants (and especially Mental Health Questionnaire completers) have better baseline socioeconomic and health status than the general UK population. We speculate that selection bias might have led our study to underestimate the mortality gap associated with mental disorders. This hypothesis is based on previous studies suggesting that the gap increases in individuals with more severe physical or mental conditions and in areas with higher social deprivation (Das-Munshi et al., Reference Das-Munshi, Chang, Dregan, Hatch, Morgan, Thornicroft and Hotopf2020; Kamphuis et al., Reference Kamphuis, Geerlings, Giampaoli, Nissinen, Grobbee and Kromhout2009; Martin-Subero et al., Reference Martin-Subero, Kroenke, Diez-Quevedo, Rangil, de Antonio, Morillas and Navarro2017).

Other limitations in our study are also worth mentioning. First, the UK Biobank did not confirm mental disorder diagnoses through clinical evaluations. This issue is mitigated in our study by the use of multiple indicators of mental disorders (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Cullen, Adams, Brailean, Breen, Coleman and Hotopf2019). Second, the UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire has modules lacking prior validation. In addition, several modules from the CIDI-SF have not been specifically validated for online application (Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Potash, Mostafavi, Battle, Zhu and Weissman2017). These issues should be addressed by future research. Third, ICD-10 diagnoses identified by hospital data linkage in the UK Biobank also lacked validation and were only captured after 1996. Fourth, although the UK Biobank is a large cohort, certain disorders were associated with few outcome events in our study. In these cases, our risk estimates were imprecise and underpowered to detect differences between groups. Fifth, we compared results obtained when mental disorders were identified by symptom-based outcomes v. hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses registered during inpatient admissions. These comparisons should be viewed with caution, as they were not validated. Thus, ‘pairs’ of disorders identified by each respective method may represent different constructs. Finally, for participants from Scotland, the UK Biobank hospital inpatient data only include psychiatric diagnoses registered during non-psychiatric admissions. Therefore, we might have underdiagnosed mental disorders in this subset of participants when using hospital data linkage of ICD-10 diagnoses.

In summary, in a large cohort of middle-aged adults in the UK, we found a higher mortality risk associated with most mental disorders identified by symptom-based outcomes and with all ICD-10 diagnoses or groups of diagnoses identified by hospital data linkage. The majority of deaths associated with mental disorders was due to natural causes. Future studies based on the UK Biobank data should continue to explore the causes and correlates of excess mortality in mental disorders, including infection by COVID-19. There is also a need for epidemiological data on psychiatric mortality in developing countries, which are scarcely available in the current literature (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Daumit, Dua, Aquila, Charlson, Cuijpers and Saxena2017).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722000034

Financial support

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) under grant number 17/09369-8 and by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) under grant number 308731/2018-2.

Conflict of interest

V. B. B. worked at Eli Lilly & Company in 2018–2019 and at Bayer Pharmaceuticals in 2019–2021, serving as a Medical Science Liaison and supporting products in the endocrinology, cardiology, and nephrology therapeutic areas. F. F. V. S. and A. D. P. C. F. have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.