In approaching the meaning of the Mari painting, I lay out its distinctive elements that help understand the image as a symbolic system. Two particular symbols are of key importance in deciphering the painting’s message, the ring and rod and the flowing vase. Both deserve special focus in the analysis of the composition. Despite many decades of scholarship on the ancient Near East, these symbols are still poorly understood. Here, I do not propose a definite explanation for either of them, but draw attention to those notions that I consider the most relevant to their meaning from a metaphysical perspective.

The Ring and Rod: Beyond Legitimacy

The Mari painting is dominated by an overall symmetry, despite the lack of the left hand border, which by and large must have mirrored the right hand one (Figs. 2 and 5). The upper register of the central panel is the only area of the composition where a predominantly symmetrical composition is absent, what Margueron has referred to as the “use of dissymmetry in symmetry.”1 This register features a scene of the conferral of the ring and rod by Ishtar on the king, who may be Zimri-Lim, although this is not certain. The group of the royal figure and the goddess facing each other is flanked by two figures of the tutelary Lama goddess. To the far right of the composition is another divine figure, recognized as such by his horned crown, whose identity is obscure.

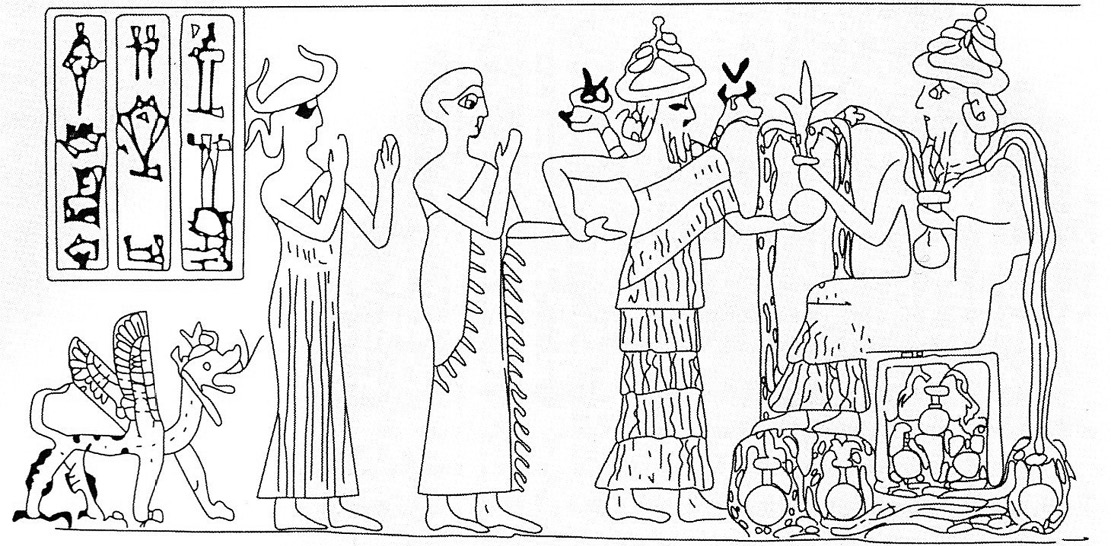

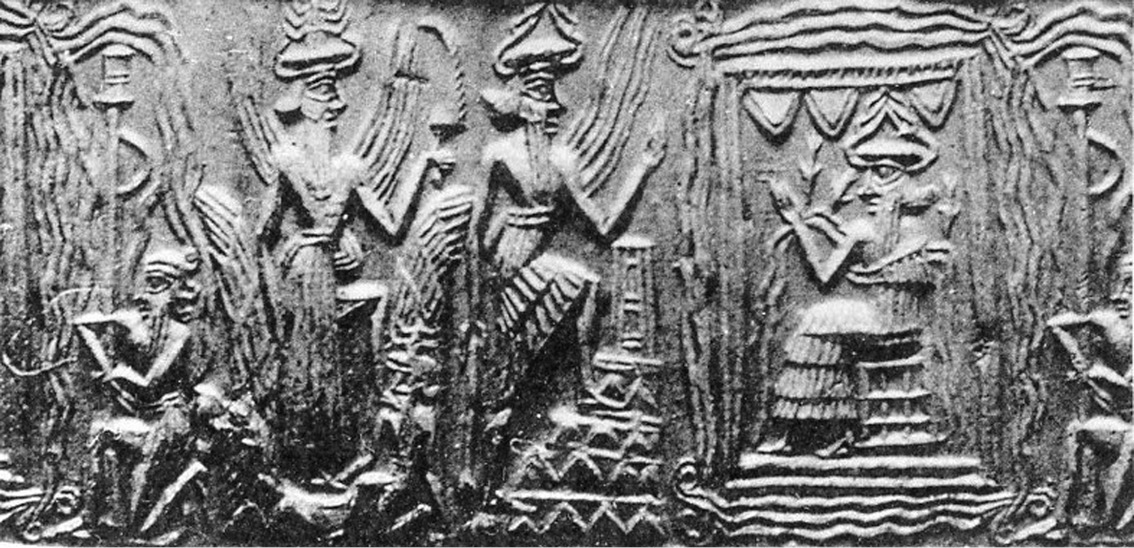

The ring and rod, often thought of as insignia of rule and authority, may be measuring or surveying instruments used in the construction of temples. Their symbolism is connected with order and harmony in the cosmos, concepts that underlie the ideology of temple building in ancient Mesopotamia as well. By virtue of their prominent occurrence in the relief on the Hammurapi Stela, they are also seen as objects with overtones of judgment or justice, notions that are cognate with those of balance and measure.2 In the visual arts, the ring and rod appear in scenes in which a god holds them, extending them toward the royal figure (Figs. 7 and 10–11).3 In light of the closer physical association of the insignia with the gods than the king, the ring and rod should be thought of as supra-royal symbols. They are part of the royal imagery, but they belong to a sphere above the king, of which the king can partake only under divine supervision.

In occupying the geometric center and focus of attention of the entire composition, its diversion from symmetry, and its featuring an encounter between the royal figure and the goddess, the upper register of the central panel is the climactic point of the Mari painting.4 It is on account of this scene that the painting has been dubbed the “investiture” in the study of the art of ancient Mesopotamia. The same formula featuring the conferral of the ring and rod by a god on the king also appears on the Stela of Urnamma from the Ur III period and the Stela of Hammurapi (Figs. 11 and 10, respectively), the latter contemporary with the Mari painting. But in discussions of neither work of art do we usually talk about, say, the “investiture” of Urnamma or that of Hammurapi.5

The first occurrence of this designation in relation to the Mari painting is in the initial excavation report by Parrot, in which the archaeologist referred to the composition directly as the “investiture” without any explanation.6 Since then, the term has been firmly attached to this work of art. The scholarly audience has hardly asked why we should think of this image as an episode of “investiture.”7 Most scholars of ancient Mesopotamia who mention the painting place the word “investiture” in quotation marks, but they do not discuss the concept in relation to the imagery. Handbooks or surveys of ancient Mesopotamian culture and archaeology illustrate, sometimes profusely, the painting or parts of it, with the discussion provided revolving around the quite general theme of the “religious legitimization” of the king.8 In this respect, it may be worthwhile to review the phenomenon of “investiture” and its relevance to the composition.

In Assyriology, “investiture” is a technical term referring to the ceremonial or symbolic conferral of royal insignia, particularly the crown, the scepter, and the throne, on the king, be it in association with coronation or not, as attested in texts. Investiture is a wider semantic category than coronation or enthronement, since in addition to ceremonies of coronation, the conferral of insignia on the king may have been part of rituals of renewal or reconfirmation of the royal office held on an annual basis, perhaps in association with the New Year’s festival. It is often unclear in texts whether the conferral is purely symbolic or connected with actual events.9 Textual accounts of ceremonies of coronation are not found in ancient Mesopotamia, except for the so-called coronation ritual from the Middle Assyrian period, a text that is not well preserved.10

Statements of the conferral of insignia on the king are especially attested in the royal hymns of the Neo-Sumerian, Isin-Larsa (ca. 2017–1740 bce), and Old Babylonian periods.11 The relevant insignia, again mostly the crown, the scepter, and the throne, do not quite correspond as objects to the ring and rod.12 Various high-ranking gods, especially Enlil, Inanna, Nanna, and Enki, are mentioned as conferring various insignia, with no consistent pattern associating specific insignia with specific deities. There is a wider spectrum of gods conferring regalia in the textual domain than there is in the visual in the representation of the conferral of the ring and rod.

At this stage, given the lack of direct correspondence between textual accounts of “investiture” and the imagery of the conferral of the ring and rod, perhaps it is best to consider, after Nunn, that the scene type is an expression of the king’s access to, or experience of, the divine at the supreme level, an access or experience epitomized by the conferral of supra-royal objects not ordinarily available to humanity.13 One may specify the nature of this access or experience as emphatically celestial, since in the visual arts it is invariably major gods with a celestial dimension, particularly the three primary celestial divinities, the sun god Shamash, Ishtar (Venus), and the moon god Nanna who are shown handing the ring and rod to the king.14

Such experience of the divine at the supreme or celestial level may be understood as apotheosis, regardless of whether or not the king was officially deified in the particular period of ancient Mesopotamian history in which the visual formula appears.15 The experience of the divine at the ultimate level, such as the scene type connotes, cannot be thought of as an ordinary affair. It would result in a major change in the ontology of the person having this experience, bringing him closer to, or even merging him with, the divine. In other words, the one who experiences the divine at this level must himself be thought of as assimilated to or absorbed by the divine, hence apotheosis.

The ancient Egyptian extension of the hieroglyph ankh, “life,” by the gods to the king is an analogous act. It represents not only the conferral of life and its renewal on the monarch, but also the process of inviting him to join the divine sphere. In this regard, remarkable in comparison to the fragment from the Urnamma Stela showing the seated Nanna extending the ring and rod (Fig. 11) is a relief scene from the Temple of Sety I (Dynasty 19, 1294–1279 bce) at Abydos showing the king making an offering to the Memphite god Sokar (Fig. 18). Despite the eight centuries separating these two relief images and the stylistic differences between ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian art as epitomized by them, there is a nearly complete systemic match between their primary elements, complete with the vessel containing vegetal elements and the royal libation poured into it. Side by side with the was scepter, standing for dominion, the ankh hieroglyph held by Sokar is the closest counterpart in the Egyptian image to the ring and rod of the Mesopotamian composition. Thus, both images show the conferral of divine qualities on the king by the gods.

In this framework, apotheosis may be implied as an ontological category within a possible body of knowledge pertaining to human destiny, and not necessarily as a rigid reflection of the contemporary political or official perceptions of the deified status of the king. Here, the king might rather stand for the model human being who is divine, or about to be divine, qualities more appropriately possessed by the leading figures among the intellectual and spiritual elites of royal courts in the ancient Near East, but always attributed or projected by them on to the king himself, or adopted officially by the king in his self-representation.

The status of a deified regal personage in the beyond as judge is attested both in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. The Sumerian poem Death of Bilgames depicts the hero Bilgames as judge over the dead in the Netherworld.16 In their presenting a path of ascent to heaven or apotheosis for the ancient Egyptian king, the Old Kingdom (ca. 2575–2134 bce) Pyramid Texts state that the dead king is not to be judged, but that he will judge.17 If the ring and rod, as potent symbols conferred by divinity on the special human being destined to be divine, are about the kind of measure, balance, and harmony that characterizes the ideal cosmic order, their possessor as judge would also perform his act of judgment by the criteria evoked and embodied by these objects. Despite its ostensibly mundane legal implications, the act of judgment evoked by the ring and rod on a monument such as the Stela of Hammurapi (Fig. 10), too, would be one that pertains to a judgment associated with a religious sphere and the beyond, just as in New Kingdom Egypt the dead are judged in the afterlife in accordance with ma’at, the true balance in the cosmos.18 As stressed by Norman Yoffee, in the epilogue of his stela inscription (l. 90), Hammurapi indicates that he was bestowed by the sun god Shamash “not with laws but with ‘truth’ (kinātum),” a word “appropriate mainly in religious thought,” referring to “law that transcends human creativity but whose suprahistorical ideals are those toward which law-makers should strive.”19

From this vantage point, the “investiture” painting is about that process of divinization or apotheosis, to which I have referred in the Introduction as the royal destiny, cast here in the guise of the royal inauguration or initiation. The resemblance here to, or evocation of, any putative protocol or ceremony of enthronement, coronation, or renewal thereof, is hence on account of these incidents’ being physical reenactments of such sacral processes in the first place, rather than their being ends in themselves.20 In the final analysis, while the scene type is not easily matched with the technical definition of “investiture” in Assyriology in terms of the specific insignia conferred on the king, it surely is to be understood as the priestly investiture, or initiation, of the highest order, the transformation of a human being into a divine man, or the god man, under the supervision of the gods. After all, underlying the “investiture” of the royal hymns of the Neo-Sumerian, Isin-Larsa, and Old Babylonian periods may be this very notion of initiation and divinization as well. Surely, then, the ring and rod are cousin objects of other royal paraphernalia such as the crown, the scepter, and the throne. We may thus come full circle; since although Parrot provided no explanation in naming the painting the “investiture,” he may indeed have been right in his perception.

The Builder King

The architectural connection embedded in the ring and rod complements this perspective, in that the ultimate royal duty is to build a temple that is meant to last under special instructions from the divine realm. This temple is often the model of the divine cosmos, whose design is supra-royal, communicated to the king by divinity. Its construction is executed on earth by the king strictly in accordance with a scheme revealed by the gods, as is clear especially in the longest extant temple hymns from ancient Mesopotamian literature, the cylinders of Gudea.21 The celestial implications of ideal sacred structures are clear in ancient Mesopotamian royal inscriptions through metaphors that compare them to mountains reaching heaven or edifices on a par with constellations.22 The sense of permanence and eternity conveyed through an architectural model is certainly of an order different from a paradisiac one expressed through a natural model, the plant and the fountain. These two archetypal models of eternity correspond to the two registers of the central panel of the Mari painting.

Gradation and Framing

After symmetry, the most distinctive visual aspect of the composition of the Mari painting is its making use of layers, either in the form of registers that contain figural representation or ornamental bands of various colors, parallel and concentric (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). In an effort to follow the visual cues in the painting to determine what they might reveal, I see this compositional strategy as signaling the stages in a particular sacral process or structure, spatial and temporal. As far as spatiality is concerned, we may think of this gradation as the levels of the cosmos traversed in a multi-step act of ascent from the terrestrial to the celestial.23 As far as temporality is concerned, the layers may represent the consecutive stages of a process, either a multi-step spiritual progress on the part of a special human being, represented by the royal figure, or one that is historical.24

The central panel of the painting and the two lateral panels that flank it have the greatest concentration of such visual use of gradation and framing. The central panel itself is an elaborate frame, constituted by six concentric bands that surround the inner scenes from three sides. The bands have varying colors, brownish red, yellowish red, and white, delineated by a total of seven lines rendered in black.25 They repeat themselves horizontally in bisecting the inner field defined by the rectangular frame. The horizontal bands that divide the two registers may be understood on the analogy of a stairway, not in the sense of their depicting an actual stairway somewhere in the Mari architecture, but a symbolic one leading from what the lower register represents to what the upper stands for. It is reasonable to think of the presence of a coloristic and numerological symbolism here as well, as discussed further below.26

The Flowing Vase: Beyond Fertility

In the lower register of the central panel, we see a field entirely different from that of the celestial goddess Ishtar (Fig. 7). This environment is an aquatic one, characterized by figures of the flowing vase. Beyond its basic relevance to agrarian concepts such as the fertility provided by river waters, especially when they are in flood, in the cultivation of the crops, the flowing vase should be thought of as a symbol of the permanently pure and pristine state of the subterranean aquatic abode of the ancient Mesopotamian god of wisdom Enki/Ea, a source of constant renewal or regeneration.

Enki/Ea’s aquatic domain is called the Apsû in ancient Mesopotamian cosmology, a realm that is part of the earth not ordinarily accessible to humanity. The close association of the flowing vase with the god Enki/Ea and the Apsû was made as early as 1919 in Albright’s article “Mouth of the Rivers” and in the 1930s’ scholarship on the art of the ancient Near East, especially Douglas Van Buren’s Flowing Vase.27 Albright recognized the image, to which he referred as the “mystic vase,” as an emphatically cosmological symbol, and saw it as a representation of the source of the subterranean or terrestrial fresh water. He understood the “mouth” of the rivers as the spot where this water “bursts into the upper world.”28 Douglas Van Buren invoked conceptions of ritual purity in addition to those of life-giving waters and fertility in an arid land in understanding the symbol.29 Moortgat understood the motif more simply as the “symbolizing of life,” and Frankfort referred to it, also simply, as “the source of all water and hence the origin of life.”30

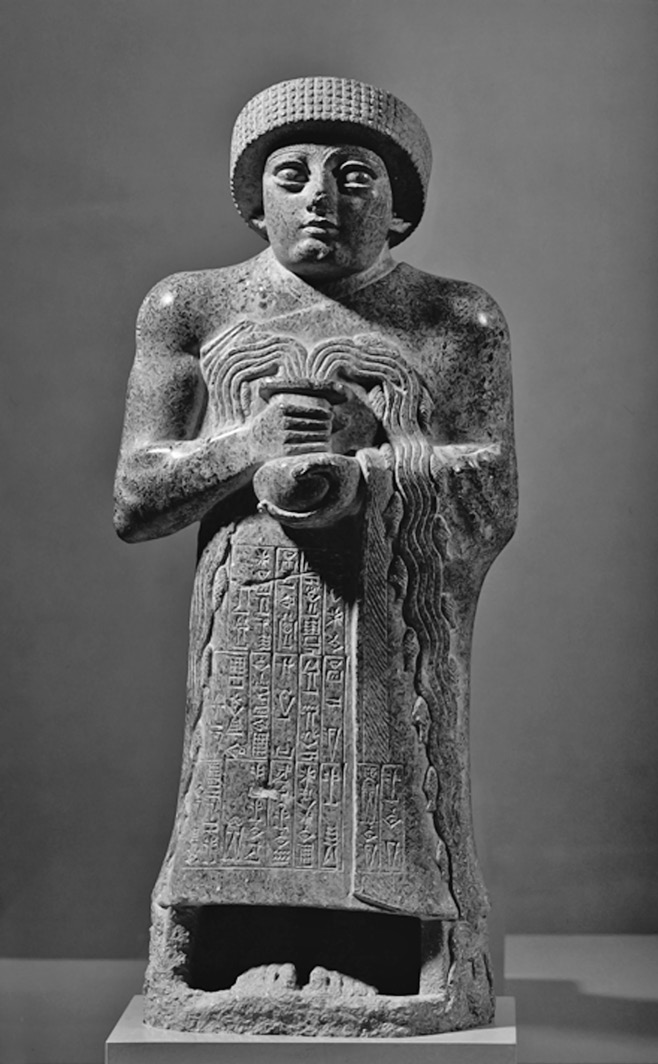

A connection between the flowing vase and paradise was drawn by Léon Heuzey in his study on the basin of Gudea from Lagash (Fig. 19).31 Like Douglas Van Buren, Heuzey, too, noted both the simple explanation of the vase as a symbol of living, gushing water and its “legendary” interpretation.32 With much greater emphasis on the latter, he elaborated on the motif’s relation to the paradise tradition, thought to be rooted in ancient Mesopotamian culture, especially in its conception of the four streams, as also noted by Parrot in his 1974 study on Mari comparing the depiction of the flowing vases in the “investiture” painting to the four rivers of Eden in the Book of Genesis.33

19. The Basin of Gudea, found in Girsu, Neo-Sumerian period. Istanbul: Museum of the Ancient Orient.

Heuzey observed that in the art of ancient Mesopotamia the vase featured either two or four streams, positing that the paradisiac idea of the four rivers was an extension of the phenomenon of the two rivers, the Euphrates and the Tigris.34 Albright, too, in his 1919 study laid out documentation for the conceptualization of both the Nile and the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in numeric paradigms of twos and fours.35 In his 1951 work, Geo Widengren also associated the two streams coming out of the vase with the Euphrates and the Tigris, and by extension with the “mouth of the rivers” of the Flood story contained in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, correlating, as did Albright, the phrase “mouth of the rivers” (pī nārāti) with that of “at the mouth of the two rivers” (ina pī nārāti kilallān) of the bilingual ritual text CT XVI in its description of the location of the mythical kiškānu tree.36

The cosmological implications of the flowing vase are particularly clear in the visual configurations in which it is found. Beyond the quadripartite depiction of the streams in the Mari flowing vases, in Assyrian art, the four streams that emanate out of the vase approximate the two diagonals drawn inside a square or rectangle with their point of intersection corresponding to the source of the water, the vase itself. Both the fragments of ivory furniture inlays from the Middle Assyrian period found at Assur and the Neo-Assyrian sculptural depictions of male minor deities holding the vase from the Khorsabad temples show this scheme.37 In a geometric consciousness that perceived the concept of entirety or universe in the form of the “four quarters,” such distinctively quadrangular depictions of the vase cannot be dissociated from notions of cosmology.38

The flowing vase is perhaps one of the most deeply mystical symbols of ancient Mesopotamia. It deserves to be studied and understood better and much more extensively than past and current Assyriology has prescribed. The engagement of the scholars of the first half of the last century with the mythical symbolism of the motif has not been carried on and developed further by later generations.39 This earlier engagement was not thorough in the first place, and with the exception of Albright’s and to a certain extent Heuzey’s, the interpretations gravitated toward literal explanations concentrating on the life-giving qualities of flowing water. The fertility of an otherwise arid land and an abundance of life-giving waters as divine gifts, to many the most immediate associations of the motif at present, were surely concepts of utmost importance in the climatic conditions of ancient Iraq. However, it would be erroneous to consider these concepts as ends in themselves and leave the symbolism of the motif there, approaching one of the most powerful emblems of the ancient Mesopotamian artistic tradition solely through the lens of climate, environment, natural resources, economy, prosperity, and the biological gift of life.

Any understanding of life on a metaphysical plane must mean eternal life or immortality. Any understanding of fertility and abundance connected with agrarian notions, especially if they are provided by the miraculous medium of tiny jugs, surely had their counterparts in a philosophical domain in which the endlessness of a pure source of water also meant eternity. It also meant the ritual purity associated with the source of that water, as well as constant regeneration, signaled further by the dual directionality established by the streams of flowing water and the fish, discussed in greater detail in the following chapters.40 In Mythology of Kingship,41 I have argued that the Neo-Assyrian relief scenes showing the winged apkallus flanking the “sacred tree” and the king may be understood simultaneously as rites of fertilization and purification, the two concepts or processes being interrelated and not conflicting (Fig. 3). I have pointed out that if one undergoes ritual purification, one reaches a new and better state or self, which can be understood metaphorically as reproducing, hence fertility, not necessarily physical but spiritual.

The notion of constant renewal expressed by the flowing vase is noted by Douglas Van Buren in her reading of the motif on the Gudea stelae as “inexhaustible abundance, and waters ever renewed.”42 Douglas Van Buren also sees the Gudea statue with the flowing vase as not showing the ruler in purely mortal guise; “fish would never swim up the body of a mortal man” (Fig. 20).43 In his comparative treatment of the art and thought of ancient western Asia and India, Coomaraswamy, too, considers the ancient Mesopotamian flowing vase from a mythical perspective as the iconographic equivalent of the Indic soma: “Iconographically, Soma can be represented either by a plant or a tree, or by the full and overflowing chalice (kalaśa = κυλιξ) from which a plant is growing; or can be thought of as an inexhaustible spring.”44 It would be naïve to think of the ancient Mesopotamian flowing vase solely as a symbol of agrarian fertility or merely as a literal manifestation of the reliance on flowing water in southern Mesopotamia.

In the study of the art and culture of the ancient Near East, particularly Mesopotamia, because of the agrarian nature of the societies that characterized civilization, scholars have been conditioned to interpret all the emblematic or symbolic visual elements depicting aquatic, vegetal, or animal motifs from prehistory on as manifestations of the fertility of the land enabled by successful governance or kingship. Few examples in the scholarship of the last several decades display any sustained interest in seeing these motifs as translations of what they depict literally into a semantic dimension other than the one defined by agriculture, abundance, and effective rule. Even those studies that have emphasized a shamanic component in artistic production during the Neolithic and Chacolithic, such as Root’s This Fertile Land and Charvát’s Iconography of Pristine Statehood, both cited favorably in the Introduction, see the religious or spiritual component of the relevant images restricted to their expressing the divine capability to ensure the fertility of the land. We need more studies of the genuine metaphysics embedded in such imagery, such as altered states, initiation, denial of death, rebirth, or liberation from the constraints of time and the cosmos.

Aquatic Endlessness

The sense of endlessness conveyed by the flowing vase is confirmed and furthered by designs that combine a number of vases in geometric systems or networks of vessels interconnected by streams (Figs. 21–22). The fact that within these configurations there often is no clarity as to the origin and destination of the flowing streams is indicative of the cyclical and magical endlessness communicated by these designs. As Douglas Van Buren puts it elegantly:

the play of crossing or intertwining lines affords boundless opportunities to the artist to cover the field with a network of exquisite and complicated patterns which seem to shimmer and dissolve, only to reform themselves into new and more entrancing designs.45

In the stela fragments (Fig. 21) and seal of Gudea (Fig. 22), we see a pattern that features superimposed rows of flowing vases in which the vases are staggered such that not one is exactly above the other, all connected by streams. In Kassite and Assyrian glyptic of the second half of the second millennium bce, aerial and terrestrial vases are linked along the vertical by streams, again with no clear sense of origin and destination.46

This source of aquatic endlessness is also a medium of access, almost a doorway, to a domain of ritual and paradisiac purity presided over by the god Enki/Ea, the Apsû itself. Indeed, the motif of the fish swimming along the streams, mostly toward the source of the water, strengthens this meaning. Fish possess agility and capabilities of navigation and access in an extraordinary realm, water, not available to many other members of the animal world either on land or in the sea. Thus, rather than symbols of animal resources and fecundity, fish connote restricted reach and access to realms not ordiniarily open to humanity. Closely connected with the flowing vase is a plant of life, again meaning immortality, which is also the object of the quest of Gilgamesh in the Standard Babylonian version of the epic, which the hero grabs in the Apsû.47 The bond between the water of life and a plant of life in ancient Mesopotamian culture and art was observed and highlighted lucidly by Albright, Widengren, as well as Coomaraswamy.48 The related “Elysian” dimensions of the Apsû were also acknowledged by Samuel Noah Kramer.49

In relation to the concept of the “sacred tree” found both in Indian and western Asian traditions, Eliade wrote: “the tree represents … the living cosmos, endlessly renewing itself. Since inexhaustible life is the equivalent of immortality, the tree-cosmos may therefore become, at a different level, the tree of ‘life undying.’”50 This statement certainly refers to fertility and abundance, but in their proper metaphysical context, as opposed to confining them merely to their literal agrarian sense.51 These paradigms have largely been ignored by current trends in the study of the art of ancient Mesopotamia and Assyriology, except perhaps solely in a historiographic sense, whereby they are treated as early antiquarian efforts to make sense of the art of the ancient Near East.52 Many of these older views, however, might be far closer to the authentic threads of meaning connecting the key motifs of this artistic tradition than their contemporary perceptions as auspicious and apotropaic images of societies with agrarian concerns inhabiting an arid environment.

In an attempt to revive the wisdom of the early scholars in understanding the art of the ancient Near East, I consider these views beyond matters of antiquarian or historiographic interest, and as possessing genuine validity in the interpretation of the visual language of ancient Mesopotamia, a premier window to the intellectual perspective of this culture. With its featuring prominently both the flowing vase and a garden, the Mari painting falls undoubtedly within the semantic domain determined by paradisiac notions. The lower register of its central panel is clearly a representation of the Apsû, even though its god, Enki/Ea, is not shown in it. As such, this register depicts a supernatural terrestrial realm.

Ishtar and Ea

Both Ishtar and Ea were part of the religion of Mari in the Old Babylonian Period.53 Even though the patron deity of Mari was Itur-mer, a political god, Ishtar in her manifestation as “Ishtar of the Palace” (Ištar ša ekallim) was one of the deities associated with the palace and its ruling dynasty.54 A festival honoring Ishtar and the royal house, which took place in the late autumn and early winter months, was the most important event in the ritual calendar of Mari during the reign of Zimri-Lim.55 This ritual entailed the introduction of the goddess into the palace and a funerary meal presented to the ancestors and members of the royal house (kispum).56 There is also evidence for the involvement of prophecy, prophets, and musicians in this annual Ishtar festival.57 The goddess was one of the chief divinities of royalty and a crucial religious force at Old Babylonian Mari.

Beyond their specific roles in the religion and ritual calendar of Mari, however, Ishtar and Ea may be present in the central panel of the painting in their basic ancient Mesopotamian symbolism, Ishtar as the lady of heaven, and Ea as the lord of a pure and primordial earth.58 Not every aspect of the palatial imagery of an ancient Near Eastern state must be understood solely in light of the ritual events taking place at or around the palace establishment. The kind of visual thinking that guided artistic production in the ancient Near East prioritized thoughts and themes additional to, or independent of, the politico-religious data available to us through the contemporary written record, such autonomy being one of the prerogatives of visual communication. Thus, Ishtar and Ea set the tone for the crucial relation between the upper register as celestial and the lower as terrestrial realms in the articulation of the cosmology of the painting.

An Aquatic Doorway

The lower register of the central panel is by and large in conformity with the symmetry that dominates the entire composition, with two goddesses holding the flowing vase, out of which emanate a central plant and four streams (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). These goddesses are different in kind from the Lama goddesses with raised hands, as the folds of their dresses are continuous in the form of uninterrupted wavy bands, paralleling in form and color the bands of the central frame. The inner ones of the farther-reaching streams of the flowing vases are connected with a horizontal stream. Swimming toward the right on this stream is a single fish, an instance of deviation from absolute symmetry.

The horizontal stream, along with the two inner farther-reaching streams from the flowing vases, defines a rectangular doorway-like gap. This gap is roughly along the same vertical axis as the figures of Ishtar and her lion in the upper register. While the upper register signals fullness and presence through the figure of the goddess, the lower register denotes void and absence through the empty space defined by the aquatic rectangle. One could see in this rectangle an echo of the entirety of the central frame whose three sides are rendered similarly with parallel lines and bands. Such parallelism may be perceived as an almost mis-en-abîme manner of concentric framing that permeates the painting.

With its paratactic clarity of action composed of five anthropomorphic figures of the same height, Ishtar’s being slightly taller notwithstanding, the upper register of the central panel is compositionally and semantically determinate. As for the lower register, with its ambiguity in the horizontal stream’s direction of flow, the presence of the central gap, and the duality in the directions in which the fish swim in the streams, it is compositionally and semantically indeterminate. I put forward the designations determinate and indeterminate as working concepts in the process of visual analysis, and not as categories of value judgment. I propose that semantic indeterminacy is a meaningful device in the articulation of the message of the painting. It is an integral component of what the lower register stands for, a zone or domain of transition and mediation vis-à-vis the upper register.

In light of the association of the flowing vase with the Apsû and the god Enki/Ea, the empty space in the lower register is an area that might be occupied by the god, were he present. Such absence on the part of Enki/Ea implies an occluded character associated with him. After all, his realm is a subterranean aquatic crypt, out of reach and out of sight. With its resemblance to a doorway, however, the empty space is also a medium of transition, plausibly from the domain represented by the lower register to the one represented by the upper, just as the flowing vase itself is a medium of access or entrance to Enki/Ea’s domain of purity. There is something “magical” about the lower register with its aquatic doorway and with what the curvilinear lines representing the streams and the fish swimming in them achieve visually. And yet, in it there is also something unfulfilled and open ended. By contrast, the upper register is static and visually less enchanting. But in it there is something firm, fulfilled, and determinate, with the ring and rod as the supreme symbols of celestial divinity handed over to the Mari king.

The Central Panel: Beyond a Rectangular Frame

The two registers of the central frame of the painting are fully separated from each other, but the doorway aspect of the lower register and the stairway aspect of the horizontal bands between them connote the availability of movement or transition from one to the other. The concentric bands that constitute the frame around the central panel signal in a condensed and abstract manner the principle of ascending gradation permeating the painting, both at the proposed spatial and temporal levels. But there must be more to the central frame; it has a somewhat iconic quality. It almost defines an architectonic enclosure, a hermetically sealed capsule, that has no ostensible channel of communication with the field outside it. Given the supernatural connotations of the overall composition, it makes sense to think of this clearly delineated central geometric statement in reference to a divine enclosure, and to look at the art of ancient Mesopotamia for a possible model.

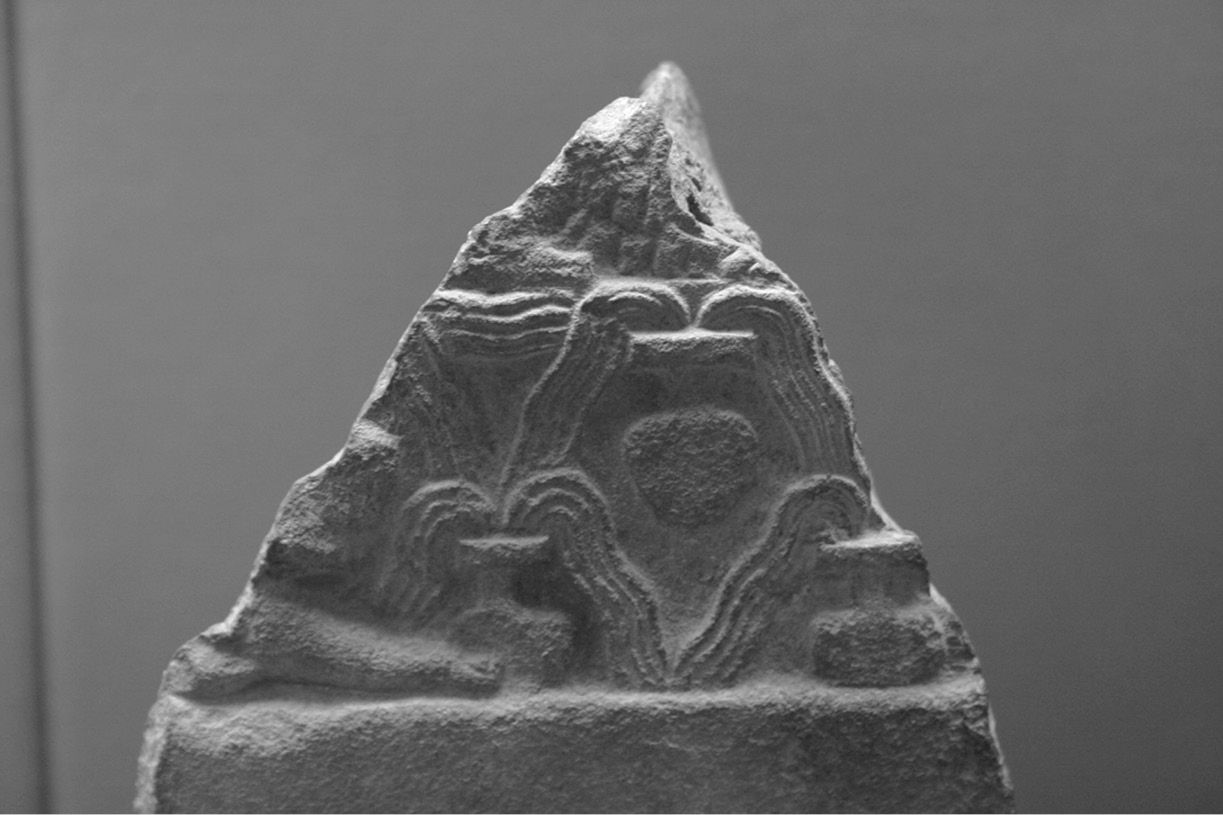

The most relevant comparison entails renditions on cylinder seals from the Akkadian period of the aquatic residence of Enki/Ea, the Apsû, shown also as a fully sealed square or rectangular enclosure, whose sides are articulated by bands and/or streams of water (Figs. 23–25). On one of these seals, in addition to an outer frame of aquatic bands, the enclosure is also characterized at its bottom by horizontal bands on which the god steps, comparable to those bisecting the Mari central enclosure (Fig. 25). In these representations, Enki/Ea is shown seated or standing inside the enclosure, with streams of water coming out of his shoulders, accompanied outside by his associates, the mythical six-curled laḫmus and his two-faced “vizier” Usmû.

24. Akkadian cylinder seal impression showing the god Ea seated inside the Apsû as a rectangular enclosure.

25. Akkadian cylinder seal impression showing the god Ea standing inside the Apsû as a rectangular enclosure with steps at its bottom.

More than half a century ago, Barrelet drew attention to the loops at the corners of some of these aquatic enclosures in order to point out a resemblance to the running spirals framing the Mari painting and to strengthen her argument that these spirals represent water (Figs. 23–24).59 What Barrelet did not take notice of, however, is the larger analogy between Enki/Ea’s abode as depicted on such seals and the central rectangular frame of the painting. This affinity is especially clear in the seal that features the horizontal step-like bands inside the enclosure (Fig. 25). None of the rectangular enclosures representing the Apsû in Akkadian glyptic, however, is bisected by central bands to yield two registers (Figs. 23–25). In the Mari painting, it is as if the enclosure of the Apsû were taken as the format for the entirety of the central frame, but then the Apsû proper were placed only in its lower register, with the goddess Ishtar and the Mari king of the upper register constituting a celestial intrusion into what in essence is a terrestrial, or subterranean, divine enclosure (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). What the artist here did is surmount the terrestrial with the celestial within the terrestrial’s own spatial confines. Rather than fully iconic, the frame of the central panel is thus diagrammatic, a visual mode that also applies, to a certain extent, to the lateral panels of the painting with their stratified levels.

Frames that are an integral part of the pictorial composition are rare in the art of ancient Mesopotamia. They characterize particularly what little remains of works of art in the media of painting and glazed brick panels, such as the examples from Dur Kurigalzu, Kar Tukulti-Ninurta, Fort Shalmaneser at Nimrud, and Khorsabad, cited in the previous chapter. In the “investiture” painting, we see clear manifestations of what Meyer Schapiro identified as frames that belong to the “virtual space” of the image rather than the image’s material surface or the viewer’s space.60 Both the frame of the centerpiece of the Mari painting and that of the running spirals around the entire composition are frames that belong to the cosmic space of the painting. As such, they are not mere organizational devices that help articulate the composition for a viewer, but they indeed represent aspects of the cosmos as ultimate boundaries, in this case manifestations of the Apsû, within the visual program of the painting.

In addressing the “histories” of framing in the visual arts, David Summers, too, invokes examples from ancient Egyptian art, in which the horizontal sky hieroglyph, supported by vertical hieroglyphs of theocratic concepts, such as the was, dominion, sets the ultimate spatial boundary for scenes of royal rituals of renewal and offering from the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom.61 Here as well, elements of frame are not simply delineations of an abstract organizational nature, while they are not fully figural or iconic either. In this respect, identifying an intermediate diagrammatic mode in the art of the ancient Near East and Egypt may be an appropriate conceptual tool in approaching the semantics of frames in these artistic traditions.

Heaven in Earth

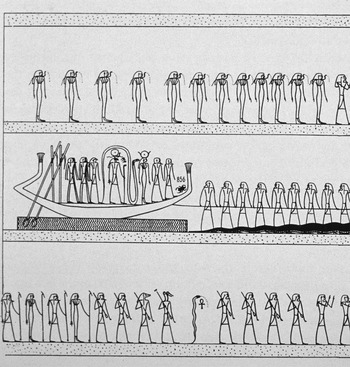

In order to clarify further this diagrammatic component in the representation of a process of renewal and ascent, one would benefit from observing a visual tradition in ancient Egypt. A number of centuries later than the Mari painting, the New Kingdom royal Books of the Netherworld inscribed and painted on the walls of the tomb interiors in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes feature just such a process of transition and ascent within a predominantly diagrammatic format (Figs. 26–27).62 This visual corpus presents notions of sacral time, eternity, and renewal in their clearest visual expression in the greater ancient Near East of the second millennium bce.

27. Drawing of the final scene of the ancient Egyptian Book of Gates, Tomb of Ramesses VI.

In contrast to the Mari painting, which makes its statement of renewal and transition from the terrestrial to celestial in one single image governed by symmetry, the Egyptian scenes of the netherworld are much more extensive in depicting step by step the journey of the sun god in the netherworld through the twelve hours of the night, especially in the earlier books of the Amduat and the Book of Gates (Figs. 26–27).63 The twelve hours start with sunset and end with sunrise. Each hour is both a temporal and spatial unit and a field of representation delineated by bands and registers. In both the Amduat and the Book of Gates, an all-encompassing frame surrounds the entire series, denoting the netherworld as an enclosure.

Even though the possible conceptions of renewal and ascent in the Mari painting are not solar, both a subterranean realm and its celestial counterpart are shown in the image. Along with the sun and the moon, the star Venus, represented by Ishtar, is one of the three principal celestial bodies of the ancient Mesopotamian heavens. As such, celestial is a broad category, of which the sun, the moon, and the stars are all part. Furthermore, the sun, the moon, and the star Venus have a degree of semantic equivalency in the art of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly apparent in the way they are treated in the upper fields of ancient Mesopotamian commemorative monuments, as disussed in greater detail in Chapter 5. Along these lines, an artificial distinction I would like to make at the outset in terminology is also one between “stellar” and “astral,” even though these two words are synonyms, the former derived from Latin and the latter from Greek.

By stellar, I refer here to stars as such, especially Venus and its standard symbol in ancient Mesopotamian art, the eight-pointed star. As for astral, I use this term in reference to implications of key celestial bodies when they bear the capacity to connote notions and realms above and beyond their own and other cosmic limitations. In other words, by astral, which I sometimes use interchangeably with “supra-solar,” particularly in the study of the Hittite double winged-disk in Chapter 5, I mean the potential in the solar, lunar, and stellar entities and images to express transcendent notions. In this respect, the three principal celestial bodies of the Mesopotamian firmament, the sun (solar), the moon (lunar), and Venus (the stellar), could all be the expression of the “astral,” should the context imply it. Thus, the basically stellar, rather than solar, character of the Mari painting should not constitute an impediment to its structural comparison to the Egyptian representations of sunrise; both delineate a step-by-step process of renewal and ultimate ascent with astral connotations.

In representations both of the Egyptian Amduat and the Book of Gates, even the final climactic moment of the nocturnal solar journey at the end of the twelfth hour of the night, the exit of the morning form of the sun god from the netherworld into the eastern horizon, akhet, is shown within the boundaries of this gigantic spatial and temporal enclosure. In the final scene of the Amduat, the morning form of the sun god, the scarab beetle, is shown inside the frame denoting the netherworld (Fig. 26). In the Book of Gates, a synopsis of the entire journey culminating in the solar ascent is depicted beyond the final gate of the netherworld, but still within the frame constituting the boundaries thereof (Fig. 27). Here, we may be observing a conceptual affinity to the Mari painting, which also utilizes what may in essence be the boundaries of a subterranean enclosure, the Apsû, rendered in an elaborate frame of bands, to accommodate the ultimate moment of the hieratic process it depicts, an ascent to heaven, expressed through the encounter between the royal figure and Ishtar.64

Rituals of renewal involving the king were celebrated on an annual basis in the cultures of both ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. The akitu festival, best documented in first-millennium bce Babylonia and Assyria, was the quintessential rite of renewal in ancient Mesopotamia. As for Egypt, the sed-festival was the long-standing medium through which conceptions of renewal and longevity were celebrated. In the New Kingdom, the opet festival observed in Thebes was also about divine (re)birth and the king’s refreshed potency.65 Not that the Mari painting is a representation of the akitu, which is only tangentially attested in the records of Old Babylonian Mari.66 Rather, it is the principle of renewal, found ordinarily in such rituals in an annually recurring mode, that may have been expressed in its key elements in this work of art. The goddess Ishtar may be present in this context not only as a palatial deity prominent at Mari, but also in her role as the divine medium of renewal par excellence, as she always was throughout ancient Mesopotamian history, including her Sumerian manifestation, Inanna.67

Both the akitu and the opet required sealed interior spaces, closed to the outside world, for accommodating the crucial phases of their rituals, the mysteries of renewal. It is only after renewal was achieved thoroughly within this enclosed space that exit from it for public acclamation took place.68 Along similar lines, both the New Kingdom Egyptian representations of sunrise (Figs. 26–27) and the Mari painting (Figs. 2, 5, and 7) show the principle of a celestial ascent within the sealed boundary of an essentially terrestrial domain.69

What the New Kingdom Egyptian representations of the netherworld achieve in up to twelve different scenes corresponding to the twelve hours of the night, the Mari painting achieves in a single composition. The Egyptian scheme lays out a terrestrial beyond, the netherworld, in both its twelve spatial and temporal phases. In the Mari painting, the gradation suggested by the six concentric and parallel bands of the central panel lays out in a vastly more condensed mode the spatial and temporal stages of an analogous process of renewal, culminating in ascent. Whereas in ancient Egypt the number twelve is clear in terms of what it represents, it is difficult to ascribe a definite meaning to the number six in the case of the Mari painting, even though an astronomical or cosmological significance is highly likely.

Perhaps, what is today enigmatic to us about this painting would have been less so had more examples of wall painting survived from ancient Mesopotamia, especially contemporary with Old Babylonian Mari, to help establish cross-references in modes of representation. But such a view, common in archaeological inquiry, should not exclude the likelihood that the Mari painting was a unique and unusual composition even in its own day and beyond in the history of ancient Mesopotamian art, the work of an innovative artist-sage, perhaps meant to be a mystery to at least some of its contemporaries as well.

The Mythical Quadrupeds: Beyond the Apotropaic

As already observed, the outer scene of the Mari painting is quite different in style from its central panel (Figs. 2, 5, and 7).

Margueron notes that while the composition of the painting is regulated by an overarching ternary system, in it there are different principles of organization at work at the same time, responding to different exigencies.70 The ternary system observed by Margueron entails the three tiers of mythical quadrupeds and the triple horizontal division of the central area of the painting, with the two figural registers of the central panel complemented by the void in the uppermost zone between the trees.71 Margueron sees an affinity between this empty space and the one defined by what I have designated the aquatic doorway in the lower register of the central panel. Furthermore, he points out the spatial and semantic continuity between the area above the central panel and the zones above the lateral panels.72

Building on Margueron’s ingenious observations on the ternary organizational system and the meaningful use of compositional voids in the painting, I would also point out an affinity among the entirety of the area between the pairs of tress, the field defined by the frame of the central panel, and that inscribed in the aquatic doorway inside the lower register of this panel, furthering my earlier simile of the mis-en-abîme (Figs. 2 and 5). The largest area in this concentric ternary scheme, the one defined by the pairs of trees, is open to the sky, just as the uppermost tier of the three superimposed quadrupeds in the side panels is also not marked by a horizontal element, even though the idea of a register defined by the figure of the top quadruped is visually understood.

The triple division of the superimposed quadrupeds corresponds in total height to that of the central frame. The same vertical dimension is divided into two in the case of the central panel, and into three in the case of the lateral panels, an observation Margueron’s analysis hints at but does not spell out. What the central panel expresses along the binary relationship between the subterranean Apsû and Ishtar’s heaven, the lateral panels convey along a ternary gradation, expressed through the differing terrestrial and celestial natures of the quadrupeds as one moves from bottom to top.

The bottom register of the lateral panels features a wingless bull, which may be human-headed, although this is not certain.73 It is shown with one of its hooves touching a roughly triangular mound rendered with the mountain scale pattern. This pattern denotes mountain or mountainous landscape in the art of ancient Mesopotamia, but it also evokes the pictographic prototype of the cuneiform sign for the Sumerian word kur, meaning earth, mountain, or the netherworld.74 The terrestrial implications of this register are obvious. In the middle register, we see a winged bird-headed quadruped, a griffin if the quadruped is a lion, touching one of its forelegs to the trunk of the tree ahead of it. This winged, bird-headed creature is certainly capable of flight in contrast to the terrestrial wingless bull. Because of the natural association of birds with trees, its contact with the tree strengthens this creature’s belonging to an intermediate domain between the surface of the earth and the far open skies, where the trees cannot reach. The top register shows a winged human-headed quadruped, a sphinx if the quadruped is a lion, not touching anything specific. Its being winged and human-headed makes it a less plausibly natural creature than a winged bird-headed quadruped, only by degree, since both creatures are after all fantastic. The human-headedness of this uppermost winged quadruped, however, imparts on it an enhanced degree of numen, making it an almost “angelic” creature that belongs to a higher heaven than that occupied by its bird-headed counterpart. Its not touching anything, coupled with its not being confined above by another ground line, is an indication of its greater ethereality compared to the bird-headed creature.

As far as wingedness is concerned, we observe from top to bottom the sequence: wing, wing, no wing; and as far as touching an element of the panels goes, we observe from top to bottom: no touch, touch, touch. It is only the intermediate quadruped that fulfills both parameters, “wing” and “touch,” and has in this regard a truly mediating quality. This intermediate quadruped is the only one in the series with a disk rendered with swirling radials inside the curve of its tail. This element is of roughly the same size as each of the spirals of the outer frame of the painting, suggesting an affinity between this intermediate level of the triple division of the lateral panels and the band of running spirals, whose mediating quality I discuss in Chapter 4.

Despite its enhanced numen and ethereality, the uppermost quadruped is by no means the equivalent of Ishtar’s heaven in the top register of the central frame, whose upper limit the figure of the quadruped does reach visually, with the sky open above it (Figs. 2 and 5). After all, an “angelic” being is not at the same level as a celestial deity. It is as though there were more distance to travel upward in the lateral panels to reach a level corresponding to that of Ishtar, perhaps signaled by the openness of the field above the top quadruped. This additional distance, however, is left insuperable and indeterminate in the painting, with the sky above the top quadruped extending indefinitely, and perhaps infinitely, upward within the picture plane. Even though two systems of gradation, binary in the case of the central panel, and ternary in the case of the lateral ones, are visually set in apposition, they represent not fully corresponding orders or systems.

The Blue Bird in Flight: The “Phoenix”?

This unresolved dimension in the lateral panels and the field above them is enhanced by the indeterminate disposition of the blue bird whose species remains unclear (Figs. 2, 5, and 28).75 Overlapping the date palm to the far right, the bird is not perched on it. It is captured in flight, but it is not clear where exactly the bird is headed, except vaguely toward the left. There is something open ended about the outer scene as well, especially in its upper field, paralleling what I have referred to as the magical quality of the lower register of the central panel. So powerful is the semiotic effect of this bird that it would be weakened, were there an exactly symmetrical pendant to it on the other side of the painting, which is not preserved.

It is clear from what remains of the painting that the composition was predominantly symmetrical, and one might inevitably ask why the blue bird in flight should not have had its symmetrical counterpart on the left hand side. However, it is also important to note that with the presence of a left-hand-side bird, the degree of symmetry in the painting would be unrelenting and perhaps counter-intuitive within the compositional rubrics both of the painting itself and the artistic traditions of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East at large. This is a parameter to reckon with in analyzing such an important work of art as the “investiture” painting; it cannot be so easily dismissed on the grounds of matters of preservation alone. Indeed, all symmetrical elements of the Mari design are of the static and hieratic type, with the only relatively more dynamic and mobile component being the blue bird. In the end, admittedly, any discussion concentrating on the uniqueness of this bird must remain speculative. However, such speculation is well worth pursuing in light of the present commitment to probe elements of the art of ancient Mesopotamia that have so far not been detected or investigated.

Thus, it is tempting to think of the bird as unique, perhaps the representation of a phoenix-like bird connected with the proposed main themes of the painting, renewal and ascent. If the bird were a unique mythological being or a symbol, it would make sense for it to be all by itself in the composition without a symmetrical counterpart. The mythical bird known in the ancient Greek tradition as the phoenix (φοίνιξ) has its roots in ancient Egypt, where it is called bnw. In Egypt, the bird is identified with the heron and associated with renewal and large cycles or periods of time.76 It is also especially linked with the annual Nile inundation, heralding with its appearance the end of the flood by alighting a tree or mound, and a new period of fertility and abundance.77 In addition to the heron, the Egyptian phoenix is also comparable to other strongly flying birds of religious importance in the Nile Valley, such as the celestial Horus in the form of a falcon and the vulture.78 Linked with the age-old solar cult at Heliopolis, the Egyptian phoenix declares the destiny of the world, “past and to come.”79 Originating from an exotic or fantastic land such as Punt, the phoenix is associated with notions of periods of time, eternity, rebirth, flight to heaven or apotheosis, and universal destiny; all concepts I propose here for approaching the meaning of the Mari painting.

On account of its intercultural connections encompassing both the Aegean and Egypt, Mari is in one of the best geographic positions for Egyptian and Western Asian traditions to have converged. R. T. Rundle Clark points out the “remarkable fact that the cult of the Bn.w [phoenix] was especially prominent along the North-east border of Egypt, i.e. where the Egyptians come into direct contact with the Asiatic peoples.”80 It is possible that the blue bird in the painting is a reference to a messenger or “angelic” being like the phoenix of ancient Egyptian antiquity, announcing the beginning of a new era, perhaps in this case one that has universal regal implications by virtue of the royal imagery at the heart of the composition.81

It is noteworthy that birds, the dove, the raven, and the swallow, are all associated with the end of the cataclysmic Flood in both the biblical and Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh narratives of the Deluge in ancient Western Asia. In the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, the Flood Hero initially releases a dove, then a swallow, both of which return without finding a perch, and finally a raven, which does not return, heralding the definitive recession of the Flood.82 As such, these birds, too, especially the one that does not return, are harbingers of the beginning of a new era. In this regard, the Mari bird, without necessarily being identified rigidly with any of these specific birds or a clearly defined mythological narrative, may be of crucial relevance to a reading of the painting in light of the paradigms offered by the ancient Mesopotamian Flood myth, as conducted in the following chapter. The Mari bird need not be in any species-oriented relationship with the heron, the eagle, the falcon, the dove, the raven, or the swallow for it to fulfill the exemplar of a bird that is the harbinger of auspiciousness at the macro-cosmic level within the symbolism of the “investiture” painting. The meaning of this bird deserves further scrutiny in relation to other representations of mythical or powerful natural birds in the art of ancient Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Egypt, which would necessitate its own study and goes beyond the scope of the present book.

The Mari bird may also be an element of shamanic lore in the painting, as may also be the strongly flying emblematic birds of ancient Egyptian religion and art. The animal most closely associated with the shaman is the bird, an animal symbolic of flight to the other world, which the shaman imitates by means of a transformative costume.83 In the ancient Egyptian royal “funerary” religion as well, as expressed by Rundle Clark:

[t]he power of the soul of the deceased to fly away from the tomb to the sky and to cross over to the land of immortality is reinforced in the Pyramid Texts by comparing the flight of the soul bird with that of various strongly flying birds or even by assuming that the soul assumes the role of one of these creatures.84

In the final analysis, side by side with the running spirals, the bird is an element speaking to the intercultural connections of the art of Old Babylonian Mari, both semantically and stylistically. Such naturalistic depictions are especially at home in the artistic traditions of the Aegean and Egypt.85 If, as I speculate, the bird is unique, with its relative scale, it would also constitute the most extreme instance of deviation from absolute symmetry found in the painting.

The affinity between the lower register of the central panel and the outer scene, especially its upper field, in terms of their shared semiotic indeterminacy once again brings to the fore the top register of the central panel as the only systematically and semantically determinate area of the painting (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). Just as the void of the inner aquatic rectangle extends inward ad infinitum, so does the outer field upward. I would posit that what we see in the outer scene is a translation into a garden or landscape form of the magical qualities of the lower register of the central panel expressed in aquatic and piscine form. Elements of determinateness belonging to the top register of the central panel do have their presence in and impact on the composition of the outer scene. Placed adjacent to the vertical edges of the picture plane are two additional Lama goddesses (Figs. 2 and 7). Beyond the goddesses is a repetition, in three vertical bands only, of the frame system of the central panel of the painting consisting of bands of color, preserved, however, only on the right hand side. If the vertical bands had their counterparts on the other side, it is as if these two features of the central panel, the goddesses and elements of the frame, had emanated outward from the focus of the painting to hold the composition together only on the two vertical sides, leaving its upper field free and open to the sky. The dynamic disposition of the blue bird enhances this openness.

Ascent to Heaven

The arboreal elements of the outer landscape are also integral aspects of the symbolism of the painting. Here we see a duality in the kind of trees. The outer are fruit-bearing date palms, the inner ones representatives of a botanically unidentified species, in great likelihood a fantastic conception. While the natural date palms are on the farther edges of the scene, the fantastic trees are much closer to the hieratic focus of the painting. The landscape defined by the pairs of trees is a formal one; the three superimposed tiers of mythical quadrupeds are confined to the area defined by the pair of trees. As such, the floor-like linear elements, on which the two upper quadrupeds stand, are stretched between the trees only. At the same time, what imparts on the outer scene the quality of a natural landscape is again its upper field. The voids here are suggestive of air or the sky, and the blue bird, no matter how incommensurate in scale with the trees, is suggestive of movement therein.

The combination of the natural and fantastic in the configuration of the trees in the painting may be thought to point to the liminal nature of this landscape. This landscape does not belong to ordinary space and time. But it also does have some connection with the natural earth and the mundane, as shown by the fruit-bearing date palms and the date gatherers tied to their trunks from their waists, as is common practice even in modern times in southern Iraq.86 This liminal quality of the landscape may be compared to that of the Apsû, since it, too, is an occluded realm ordinarily out of reach, but still part of the earth. If the lower register of the central panel is a representation of the Apsû, then the element of the plant that is part of the flowing vase points to a vegetal, in addition to aquatic, component in the representation of this realm. The landscape of the outer scene could then be thought of as the materialization in much grander scale of the vegetal, or arboreal, component of the Apsû.

An aquatic element is not absent from the outer scene and its landscape either. As Barrelet proposed, the band of running spirals surrounding the entire composition may have aquatic symbolism.87 It is not uncommon in ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian representational systems to superimpose an elevation or profile view of figures in an enclosure on a view in plan of that enclosure. The band of running spirals framing the outer scene may well be thought of on the analogy of a stream of water surrounding a garden.88 While the streams of the flowing vase may be understood as water in the figural mode, the running spirals of the outer frame may be understood as water in the ornamental mode (Figs. 2, 5, and 7).

The distinction between a figural and ornamental mode in the representation of water in the painting must also point to a difference in the attributes of water expressed in each instance. Whereas the figural streams denote more directly a definite aquatic environment of a supernatural character, the ornamental mode refers to an aquatic principle permeating or surrounding the cosmos, a source of regeneration and an all-encircling boundary. Just as the lower register of the central panel, the aquatic Apsû, establishes the foundation and support for a graded ascent to the celestial domain of Ishtar through the conceptual stairway, so does the arboreal manifestation of the Apsû in the outer scene signal an analogous process of ascent through the tiers of the quadrupeds it holds together. With an almost structural link established by the horizontal tiers, the pair of trees is again a diagrammatic unit in laying out the principles of the ternary gradation analyzed above (Figs. 2 and 5).

In light of the presence of two different systems of gradation along the vertical at work here, while the medium of ascent from the foundation established by the Apsû to Ishtar’s heaven in the central panel, the horizontal bands, is like a solid stairway; the medium of ascent in the lateral panels is like a ladder constituted by the trees and the ground lines that connect them as if they were rungs. A ladder is an object very different from a solid stairway, but the purpose behind both climbing tools is ultimately the same. In holding together the stairs and the rungs, the lower register of the central panel and the upright trees, respectively, may once again be viewed as one another’s semantic equivalents. They may both be seen as representations of the Apsû as an intermediate domain in supporting and enabling ascent.

This mediating capacity of the Apsû should be seen in its being connected to the earth at large and constituting a realm that is divine and supernatural, without being on a par with the celestial community of the gods. If we look at the ternary gradation of the lateral panels from this perspective, we see the intermediate tier with its bird-headed winged quadruped in such a mediating role between the earthbound bull and the human-headed numinous creature that marks the beginning of the heaven stretching indefinitely above it (Figs. 2 and 5). By touching one of the trees, notably the fantastic one, this intermediate quadruped reveals its affinity to the Apsû in its arboreal manifestation. By featuring a disk with swirling radials inside the curve of its tail, it reveals the same affinity with the alternative aquatic manifestation of the Apsû in the ornamental mode, found in the frame of the running spirals.

Coloristic Symbolism

Each of the elements of the ternary gradation of the lateral panels may have corresponded to a distinctive aspect of the cosmos and the divine as perceived in Old Babylonian Mari.89 A ternary division of both the earth and heaven in Babylonian cosmography is the case in first-millennium bce texts, pointing at least to the fact that such a configuration is at home in ancient Mesopotamian thought, and could predate the first millennium bce.90 In his discussion of the identity of the stones that constitute the substance of the three heavens based on these texts, Wayne Horowitz indicates that the luludānītu-stone, of which the upper heaven is composed, is a reddish stone with white and black patches.91 The Middle Heaven is identified with the saggilmud-stone, which is a stone the same color as lapis lazuli.92 As for the Lower Heaven, it is composed of jasper, “a type of chalcedony, a hard, glassy, often translucent stone.”93 The predominance of the colors red, white, and black in the concentric bands that establish the frame of the central panel of the “investiture” painting and the use of blue in the background especially of the “investiture” scene proper inside the central panel may be loaded with such coloristic symbolism that pertains to the geography of the ancient Mesopotamian heavens.

Especially the colors associated with the Upper Heaven, red, black, and white, are found not only in the bands of the central panel, but also in the wings and garments of the mythical figures inside and outside the panel, as if all together they signaled the highest heaven in the cosmological set-up of the composition. As for the background of the figural scenes preserved, there is a predominance of patches of blue, the color of the Middle Heaven, on account of its association with lapis lazuli. According to the Neo-Assyrian text KAR 307, the Middle Heaven contains the lapis lazuli cella of the ruler of the cosmos, Bel/Marduk, the successor of Enlil as lord.94

A parallel interpretation of the basic coloristic scheme, or the traditional palette, of the ancient Mesopotamian painter, consisting of red, black, and white, comes from Charvát, who associates its occurrence on the Halaf-period (ca. 5600–5300 bce) pottery from Tell Arpachiyah in northern Iraq with the same paradigms of cosmology, the uppermost heavens belonging to the god An and the luludānītu-stone that constitutes its substance.95 Charvát boldly traces the veneration of the sky god An and the origins of ancient Mesopotamian cosmology to the Halaf period, seeing the three colors appearing frequently on the pottery as “a more widely conceived spiritual construct.”

If the notions expressed in first-millennium bce texts can plausibly be seen to have relevance to the prehistoric pottery of ancient Mesopotamia, all the more reason to consider works of art of the second millennium bce as part of such a continuum, rather than as chronologically divorced from any cultural aspect of the first millennium bce, as though there were an impermeable wall between these two modern “millennial” formulations. As Horowitz aptly puts it, “in many respects, ancient Mesopotamian understandings of the universe remained remarkably constant over 2,500 years or so from the earliest evidence for cosmography in literary materials through the end of cuneiform writing.”96 Indeed, the thirteenth-century bce wall paintings from Kar Tukulti-Ninurta, too, feature the same traditional palette consisting of red, black, white, and blue, extending this coloristic spectrum from the Middle Bronze to the Late Bronze Age.

Stairway to Heaven

The concept of a stairway or ladder reaching heaven is not absent in ancient Mesopotamian texts relating myths of ascent from the second half of the second millennium bce and the first millennium bce, especially the Etana Epic. In this poem, a ladder seems to be featured previous to Etana’s ascent to heaven.97 References also exist in texts to the daily ascent of the sun god to heaven from the netherworld, in which the god climbs a stairway of lapis lazuli.98 The image of a ladder as a medium of ascent can especially be seen in the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom, relating in highly complex terms the rise of the king to the celestial realm for apotheosis.99 Osiris as the god of the terrestrial beyond is especially active and effective in enabling this ascent, and in certain instances he himself is the one who ascends.100 In noting the gradual ascent of the tribute processions to the presence of the Achaemenid Persian king in the reliefs lining the stairs at Persepolis, Root points out how the candidates for access to the Egyptian beyond climb a similar gently rising stairway to reach the presence of the god Osiris for judgment, as shown in the wall paintings inside the tomb of Horemheb (Dynasty 18, 1323–1295 bce) in the Valley of the Kings.101

Closer to home, the quintessential manifestation of the principle of a stairway and ascent to heaven in ancient Mesopotamia is the temple tower, the ziggurat, examples of which dominated the skylines of Babylonian and Assyrian cities from the third through the first millennia bce, although Mari did not have one.102 Given its familiarity with and participation in the Babylonian cultural sphere, Mari’s not having had a ziggurat should not constitute an impediment to the relevance of the symbolism of the stages of a ziggurat to the sense of linear gradation found in the composition of the “investiture” painting. With their different levels, possibly featuring different colors, the ziggurats were perhaps the most enduring manifestation in ancient Mesopotamia of a principle or process of ascent to heaven within a meaningful system of gradation across the cosmos.103

The following chapter focuses in greater detail on the terrestrial background of ascent to heaven, or apotheosis, as possibly expressed in ancient Mesopotamian art and thought. It sustains the focus on the Mari painting, and offers a reading of its composition and imagery against the backdrop of the Babylonian Flood narratives as paradigms for the establishment of terrestrial realms of longevity and immortality as well as those for sacral time and eternity. To that end, it attempts to further the discussion conducted here regarding the priestly “investiture” of the Mari king as an epitome of immortalization or apotheosis.