Introduction

The confrontation between the Crescent and the Cross in the early modern (c. 1500–1800) Mediterranean is well documented (e.g. Williams Reference Williams2014). A key component of this conflict was captivity and the threat of enslavement. Land and seaborne slaving raids enabled Christian Europeans to snatch Muslims, while Barbary and Ottoman pirates pillaged Christian lands and vessels. Chief among the European powers forging this war were the Order of the Knights of St John—a Catholic military order established in the middle ages—and their licensed corsairs. After Ottomans forced the Knights to flee their base on the island of Rhodes, they settled in Malta in 1530, where they reigned until expelled by Napoleon in 1798 (Blouet Reference Blouet1967). Many other groups were embroiled in this struggle, including Jews and Greek Orthodox Christian traders sailing under the Sultan's flag. Published narratives, as told by those who found freedom from captivity, enliven our image of a sea full of danger. Yet most of these accounts of Mediterranean captivity were authored by noble, clerical or administrative men captured at sea, the majority of whom were European Christians. While individual historians have in recent years made much use of this textual record (e.g. Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith2010; Greene Reference Greene2010; Weiss Reference Weiss2011; Hershenzon Reference Hershenzon2018), accounts of slavery and other forms of early modern Mediterranean captivity are frequently “de-emphasized as uncertain, unreliable, aberrant and specific” in the broader historiography of slavery (Taylor Reference Taylor, Pearson and Thorpe2005: 225). Major, standard works, including The Cambridge world history of slavery, demonstrate this point, with the latter offering only a single chapter on enslavement in the Ottoman Empire (Toledano Reference Toledano, Eltis and Engerman2011)—all but erasing slavery controlled by Southern European Christians. The daily lives of captives, along with the ramifications of forced mobility and cultural interaction, are, however, essential for understanding the development of the modern Mediterranean. While the scarcity of historical accounts written by the fishermen, peasants and sailors who also found themselves long-term captives may impede the work of historians (Davis Reference Davis2003: 34), archaeologists are well placed to investigate the daily lives of slaves, convicts and other unfree people (Cameron Reference Cameron and Cameron2008: 19). This article turns to the archaeological evidence from early modern Malta (Figure 1), the island group at the centre of the Western Mediterranean where captivity and the threat of enslavement were omnipresent.

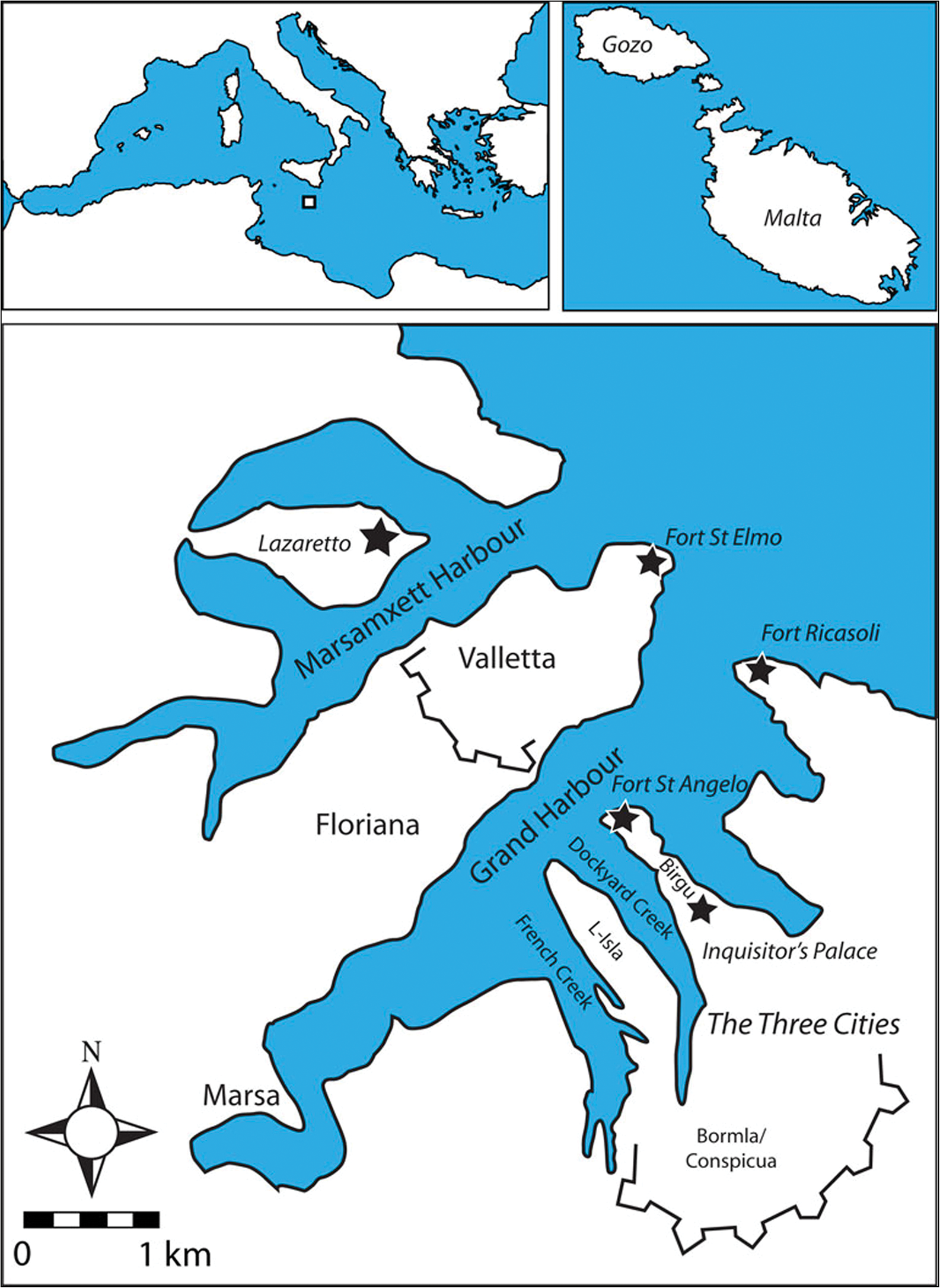

Figure 1. Location of Malta and the main sites in the harbour area (image by R. Palmer).

Direct evidence of captives is rare in archaeological contexts, and the “obvious tools of domination such as shackles or chains” are infrequent finds (Marshall Reference Marshall, Cameron, Harrod, Gijanto and Martin2014: 5). When skeletal remains of putative captives are available for study, bioarchaeologists have developed ways of successfully investigating the “bony diaries of people's lives” (Tung Reference Tung, Martin, Harrod and Pérez2012: 180). The musculoskeletal stress of repetitive actions associated with demanding physical labour, and the recidivist nature of violence frequently enacted against captives, can leave identifiable traces on bones (Martin Reference Martin and Cameron2008: 162). These can suggest that a person was a captive, and can illuminate the treatment of captives and their social place in death. Human remains, however, are not the only source of archaeological evidence for captivity. In plantation archaeology, the “everyday living conditions under slavery and expressions of cultural identity” (Singleton Reference Singleton1995: 123) have long been important themes of research, but it has not always been clear how the archaeologist might proceed when investigating sites where clear evidence for captivity does not appear to exist. Recent studies demonstrate how captivity, which is often considered “difficult to see in the archaeological record” (Cameron Reference Cameron and Cameron2008: 20), may be revealed. By reconceptualising captivity as a process, rather than as a ‘thing’ (i.e. people or objects signifying captivity), and integrating its existence with other societal phenomena, we can glimpse captivity “indirectly through its effects on a range of practices” (Stahl Reference Stahl and Cameron2008: 39).

Ben Raffield (Reference Raffield2019: 695) has recently employed such a conceptualisation in his investigation of Viking slave trading. Highlighting the pervasiveness of slavery in Viking society, he argues that a “focus on ‘proxies’ for slave trading within broader mercantile contexts” is more productive than looking for sites and objects that more obviously signify slavery and slave markets. The Viking context shares several features with the early modern Mediterranean, in which many slaves were taken in raids and battles to form part of the labour economy and were thus immersed into everyday society. A particularly important part of Raffield's approach is his acknowledgement of the potential benefits of reinvestigating previously analysed sites and assemblages. Employing this approach allows us to revisit old evidence with a more sensitive interpretive predisposition (Taylor Reference Taylor, Pearson and Thorpe2005: 225). With captives in mind, we may be able to follow the material processes of enslavement and forced labour, re-envisioning captives not only as victims, but as active agents who often engaged with their captor's society and who had the ability to bring about social change (Cameron Reference Cameron and Cameron2008: 19; Stahl Reference Stahl and Cameron2008: 38).

A final important and challenging issue derives from the language and definitions that we use to describe various states of ‘un-freedom’. While historians frequently discuss slavery in isolation from other forms of captivity, specific legal definitions are not always helpful when assessing the material traces of unfree people. I build on Taylor's (Reference Taylor, Pearson and Thorpe2005: 230) argument that the primary essence of slavery lies in the “colonized body” in order to define captives as those who have been taken from their natal society by raiders, or members of a captor society who have been denied freedom by their society's legal, religious or social institutions—all of whom benefit the captor society through their labour. Such a definition of captivity is pertinent to the situation on board a Maltese galley, where the material culture of one rower may look very similar to another, regardless of their legal status or religion. Although historians may claim that the treatment of rowers in the Knights’ navy “is difficult to judge owing to the paucity of primary sources” (Muscat & Agius Reference Muscat, Aguis and Agius2013: 378), through material remains, I show here that archaeologists can access aspects of rowers’ lives at sea. Furthermore, I trace captive rowers on land by considering them as part of the wider Maltese society. Reconfiguring Mediterranean captivity as a process helps to remove the intellectual blinders that have hitherto obscured its existence in the Maltese archaeological record. The excavations of the sites discussed in this article were not motivated by research questions about captivity, but nonetheless yield significant information about captives and their consequences, when approached with an appropriate interpretive lens.

Captives and captivity in Malta

The size of the slave population in Malta varied over time. During the seventeenth century, it is thought to have accounted for between three and four per cent of the population. In 1632 around one third of slaves (649) in Malta laboured in land-based occupations, including in dockyard industries and private residences; the remainder (1284) served on the galleys (Brogini Reference Brogini2002: para. 21). Women comprised only ten per cent of the slave population, and, of the men, 80 per cent were non-Christian—predominantly, though not exclusively, Muslim. Small numbers of Jews from the Levant and cities such as Venice joined Christians from Egypt, Syria and Central Europe, along with Greek Orthodox Christians from Ottoman lands. The majority of Jews and Christians, along with many Muslims, were captured en route to or returning from Alexandria (Brogini Reference Brogini2002: para. 8–16). The slave economy underpinned the Knights’ hegemony in Malta. In addition to the indirect financial benefits of unpaid captive labour, the Knights profited from selling slaves at the markets in Valletta (Malta) and Livorno (Tuscany), and from ransoming wealthier captives. The potential return on ransoming could be high (Kaiser & Calafat Reference Kaiser, Calafat, Trivellato, Halevi and Antunes2014: 125), and was not restricted by the religion of the captive person. Jewish ransoming societies in Venice and Livorno, for example, succeeded in reclaiming many enslaved Jews from Malta, establishing cemeteries for those they failed to ransom back (Cassar Reference Cassar2014: 177).

The Knights were not alone in their slaving endeavours, and captor could quickly become captive. The threat of slave-raiding parties was omnipresent in the lives of coastal-dwelling and seafaring Maltese. In the summer of 1551, Gozo—the smaller sister in the Maltese archipelago—lost around 5500 inhabitants to slaving raids orchestrated by Barbary corsairs, almost depopulating the island (Blouet Reference Blouet1967: 90). The primary response of the Knights was to secure the islands through a system of coastal towers, in a similar fashion to other Mediterranean states. Southern Italy, for example, had over 500 such towers, and in Sicily the distance between towers averaged only 8–10km (Davis Reference Davis2003: 38). Although many were fitted with limited ordnance, the primary purpose of these towers was surveillance. In Malta they were used to alert the navy to the impending danger (McManamon Reference McManamon2003: 45).

During the seventeenth century, successive Grandmasters—leaders of the Order of the Knights of St John and rulers of Malta—built coastal watchtowers that formed a line-of-sight signalling system connecting Gozo and the Maltese coastline with the Grand Harbour (Figures 1–2). These towers were manned day and night by a chief-guard plus three other guards, each recruited from the general population. They usually quartered together in a single room in the tower (Figure 3). Officially, a knight oversaw the running of each tower, although an inspection in 1743 found a knight in charge at only one tower; that serving time at a watchtower was often issued as a punishment to knights demonstrates their apathy for the role (Muscat Reference Muscat1981: 104–106). By the mid eighteenth century many of the towers were in an “overall state of abjection” (Spiteri Reference Spiteri2017: 182).

Figure 2. Map indicating the approximate locations of Malta's coastal towers: Wignacourt, AD 1601–1622 (red stars); Lascaris, AD 1636–1657 (orange dots); De Redin, AD 1657–1660 (yellow squares); Cottoner, AD 1660–1680 (green hexagons) (image by R. Palmer).

Figure 3. Ħamrija Tower, built by Grandmaster Martin de Redin and completed in AD 1659 (photograph by R. Palmer).

Some of the many coastal watchtowers built along the Northern Mediterranean shoreline have been the subject of archaeological investigation. Archaeologists have explored Sardinian coastal towers using excavation and investigative restoration (Serra et al. Reference Serra, Vargiu, Cannas and Avilés2017), and in Sicily, Kirk (Reference Kirk2017) has examined the motivations for building coastal watchtowers and the communication links between them. The latter project assigns piracy a partial role in the early modern transition from inland to coastal defences, yet neither of these two studies directly addresses the significance played by the threat of captivity. Built to protect the islanders, Maltese towers represent an important material manifestation of the process of captivity. The correlation between their dilapidation and a general decrease in the threat of coastal raids suggests that their primary purpose had passed by the late eighteenth century. In the preceding 200 years, however, they formed a line of protection via their role in forewarning inhabitants and communicating the danger to the galley fleet, which could launch a counteroffensive.

Galley captives at sea

Although galleys spent most of their time cruising under sail, oarsmen propelled the vessels for many consecutive hours if giving chase or fleeing from trouble. The average crew therefore included many rowers. A seventeenth-century Maltese galley, for example, carried around 20 knights and officials, 180 sailors and soldiers, and 280 rowers spread equally among 52 oars and 26 benches (Grima Reference Grima1979: 52–53; Wettinger Reference Wettinger2002: 340). The Knights employed a small number of free mercenaries, but the majority of rowers were captives. These captive men comprised: slaves, most of whom were Muslim; convicts (forzati—literally ‘forced men’) sentenced by the civilian and religious courts of Catholic Europe to row as punishment; and debtors (buonavoglie), who had elected to row in order to pay off their obligations, but were captives nevertheless for the duration of their indenture. All three groups comprised men who were chained to their benches. The convicts condemned to row for life were, in effect (if not in law), as socially ‘dead’ as slaves (Mucat & Agius Reference Muscat, Aguis and Agius2013: 370). In 1632 the fleet's rowers comprised 1846 slaves, 175 convicts and 387 debtors (Wettinger Reference Wettinger2002: 340–41). Buttigieg (Reference Buttigieg, Colombo, Massimi, Rocca and Zeron2018: 290) suggests that a balance of captive rowers was preferred in order to avoid having too many Muslims on board.

Rowing a galley requires immense strength and stamina. The gruelling routine entailed “one of the most brutal forms of slave labor ever devised” (Davis Reference Davis2003: 75), a role for which not every captive was suitable. When selecting slaves, knights looked for healthy, robust and tall men between the ages of 18 and 30 years (Williams Reference Williams2014: 113). Distinguishing marks and bodily defects were all assessed: smooth-skinned hands could indicate a rich person and therefore someone worth ransoming, whereas circumcision was used to classify a man as Muslim, or at least non-Christian, and therefore as a legally taken captive (Davis Reference Davis2003: 62; Muscat & Agius Reference Muscat, Aguis and Agius2013: 371). A captive's body was also marked by his captors to indicate his status. A Muslim slave, for example, “had to retain a beżbuża or forelock as recognition of his social condition”, and Christians wore a moustache (Muscat & Agius Reference Muscat, Aguis and Agius2013: 376). Visual marking, however, did not alter the fact that whether Muslim, Christian or Jew, the sale and circulation of unfree labour in the Mediterranean world made captive galley rowers all but indistinguishable from each other in terms of their lives and their possible routes to freedom (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2009: 32).

Rowing also affects the skeleton. Osteoarchaeological research has identified a putative late sixteenth-century galley oarsman in Alghero, Sardinia, through the correlation of musculoskeletal stress markers with those probably caused by the biomechanically demanding and repetitive motions enacted by a rower (Giuffra et al. Reference Giuffra, Bianucci, Milanese and Fornaciari2013: 445–58). Mortuary remains unearthed in 2012 in Marsa, Malta, would benefit from a similar appraisal, as archaeologists of the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage believe that the remains indicate the presence of a Muslim slave cemetery and associated mosque (Pace Reference Pace2012).

As human remains may not be present or accessible, we can look elsewhere for evidence of galley rowers’ lives. Two wrecks excavated off the coast of Turkey are potential places to start: wreck TK06-AD, a late sixteenth- to seventeenth-century Ottoman sailing vessel (Royal Reference Royal2008: 93–95) and wreck TK05-AB, a smaller, probably Ottoman, galley (Royal & McManamon Reference Royal and McManamon2009: 104–108). Although neither wreck has so far produced direct indications of captives, such as shackles, the sites offer the potential for a wider reassessment of Mediterranean captivity. In Malta there are no known similar wreck sites to explore, but relevant evidence exists in the form of a harbour deposit.

In 2002, Timmy Gambin (Reference Gambin2003) led an underwater survey of Dockyard Creek, an inlet of the Grand Harbour that was home to the Knights’ galley fleet (Figure 1). An area located in front of the Maritime Museum and adjacent to Fort St Angelo produced an assemblage of finds dating primarily to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (site DC02, zone B). As the creek was chained off during the Knights’ period, merchant and other maritime traffic was restricted to other harbours. We may assume, therefore, that these finds relate to the Knights’ galley fleet and were lost or discarded during repairs (careening), the pumping out of bilges, or in occasional historically documented instances of capsize during stormy weather (Brydone Reference Brydone1773: 334). The assemblage comprises 739 finds, most of which are ceramics (88.2 per cent by sherd count and 97.7 per cent by weight). The assemblage also includes a range of bone artefacts and ecofacts (Palmer Reference Palmer2017: 202), which, together with the ceramics, allow investigation of the consumption habits and pastimes of those on board.

The ceramic assemblage comprises a broad range of fragmentary vessels related to consumption, including elaborately decorated polychrome maiolica and plain earthenwares. Rowers ate and slept at their benches, and were provided with food. Over ten per cent of ceramic vessels are small, plain Maltese earthenware bowls that would suitably hold the primary diet of soup with bread or ship's biscuit (for a detailed discussion of a galley crew's diet, see Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 145–52). A few bowls have been scratched on the base and others show evidence of repair. As rowers had few or no personal possessions beyond those issued to them, such marking and repair practices point to an on-board economy in which everyday bowls become prized, as well as essential, belongings (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Scratched and repaired bowls from Dockyard Creek (figure by R. Palmer).

While a preponderance of smaller bowls may indicate individual eating habits, there is also potential evidence that rowers may have socialised on board. The presence of 34 bone and stone dice indicates the playing of dice games and gambling (Figure 5). The occurrence of worked mammalian long bones (probably from the live pigs and sheep taken on board for consumption) demonstrate that the crew, including rowers, spent many hours carving dice, possibly while smoking (Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 196). Turkish chibouk pipes suitable for tobacco-smoking feature prominently in the assemblage, comprising 72 bowls, and including three of the type suitable for smoking hashish (Wood Reference Wood2008: 9). Tobacco was often issued to rowers and perhaps so too were pipes, although unlike the eating bowls, no pipe bowls bear obvious marks of ownership.

Figure 5. Finds from Dockyard Creek: a) bones partially worked into dice; b) bone and stone dice; c–d) three-hole grated ‘hashish’ pipes; e–f) Turkish chibouk pipe bowls (figure by R. Palmer).

Galley captives on land

Galleys had a relatively short sailing season, which means that galley rowers—slaves, convicts and debtors—spent around six months of the year on land. Large seaborne workforces turn into a potential security problem when they need to be housed in densely populated urban areas; the Mediterranean solution was the bagno, or slave prison. The first large-scale European bagni were built at the turn of the seventeenth century in Livorno and Valletta—the latter of which augmented and, to a large extent, replaced two smaller slave prisons located either side of Dockyard Creek (Wettinger Reference Wettinger2002: 85–87). Drawing on Ottoman and North African models, the European bagni comprised not only prison cells, but also dormitories, infirmaries and mosques (Hershenzon Reference Hershenzon2018: 132). The Valletta bagno also became the principal convict prison, housing both slave and convict rowers when on land, albeit separately. Slaves and convicts also had their own taverns at the prison. Penal reformer John Howard described it as a place in which slaves conducted a “woollen manufactory” and worshipped according to their religion in “chapels or mosques” (Howard Reference Howard1791: 53). Although not free, captives could, to some extent, carry on their own businesses, selling the goods they produced, and maintain their religious lives and communities. This has led historians to suggest that despite enduring a tightly controlled daily life, captives nevertheless found opportunities to socialise, meeting in poorly policed places and forming active networks of solidarity (Brogini Reference Brogini2002: para. 48; Salzmann Reference Salzmann2013: 392). Neither the bagno in Valletta nor the smaller slave prisons near Dockyard Creek survive today, as they were destroyed by bombing during the Second World War.

The Roman Inquisition also incarcerated galley rowers as part of their regulation of the wider population. Just as historians recognise Inquisition records as a primary source for the history of slavery in Malta (Buttigieg Reference Buttigieg, Colombo, Massimi, Rocca and Zeron2018: 287–88), archaeologists must seek out the material remains of this and other such places where captives spent time. As an institution dedicated to regulating the correct observance of Catholic doctrine and social behaviours, the Roman Inquisition did not actively pursue Muslims or Jews. Many Jews and Muslims, however, converted to Christianity—whether out of convenience or genuine religious commitment—and found themselves investigated for apostasy, or, perceived as pedlars of mystical superstitions, they were denounced as sorcerers (Ciappara Reference Ciappara2001: 89–91). The exact proportion of rowers who were Inquisition inmates is not precisely known, although between 1744 and 1798, records show that of 147 prisoners, 55 (38 per cent) are possible candidates. The Knights’ slaves numbered 29, and comprised 19 North African Christians, who were most likely converts, nine Muslims, and one Jew from Gibra. Hac Hajmi, slave of the innkeeper at the bagno, is among six private slaves recorded, along with 19 convict rowers from Sicily and the Italian Peninsula (Ciappara Reference Ciappara2001: 525–59). The Inquisitorial headquarters, including its torture chambers and prison, were located in Birgu, a few minutes’ walk from Dockyard Creek. Not only do extant prison cells and architectural plans provide a context of captivity available for investigation (Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 52–59), excavations of a prison cess pit have unearthed finds that can illuminate the lives of the incarcerated.

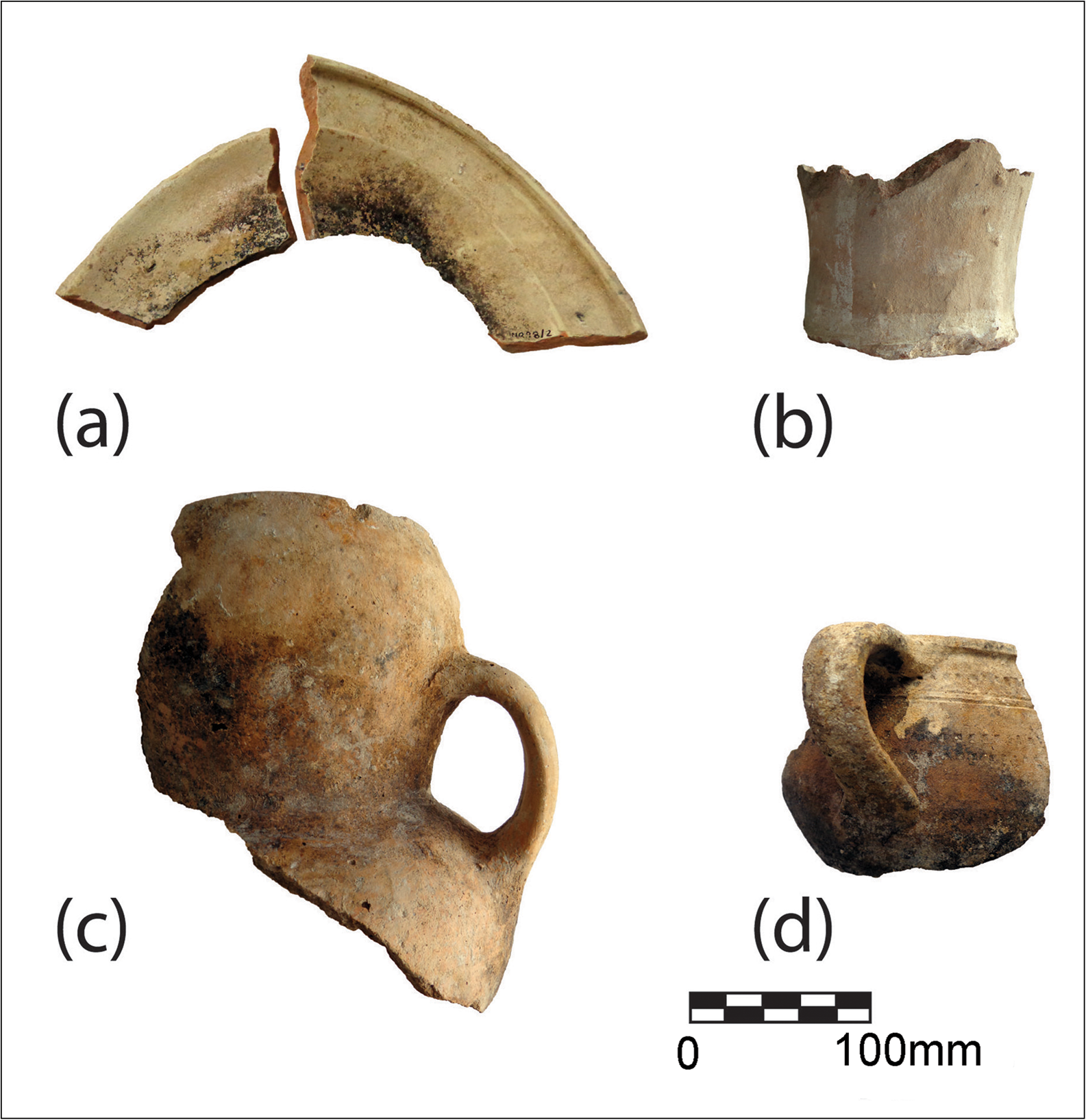

The prison-phase assemblage from the cess pit comprises almost exclusively ceramics (98.1 per cent by weight), the majority of which relate to the preparation and consumption of food and beverages. The presence of local earthenware braziers and vessels with sooting on their undersides indicates cooking activities within the prison's communal cells and courtyard (Figure 6). It is entirely likely that prisoners cooked and ate with their cellmates. Such artefacts and eating patterns befit a soup- and bread-based diet that mirrors the evidence at sea and historical descriptions of most islanders’ diet (for more on Maltese diets, see Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 131–58). The ceramic assemblage also contains evidence for lamps and lanterns—mostly locally made and commonplace (Figure 7)—that suggest the presence of artificial light in communal cells, rather than complete darkness during the long Mediterranean nights. Non-ceramic finds include copper-alloy buttons, a stone counter inscribed with a number ‘2’, part of a wooden brush-head, a piece of bone that has been worked into a rudimentary comb, a bird's talon and a human tooth (Palmer Reference Palmer2017: 141). The single forelock of hair assigned to Muslim slaves may mean that combs and brushes are unlikely manifestations of their material culture. They could, however, have provided rare moments of humanising personal care for other captives. The stone counter suggests a form of gaming that resembles the entertainment found aboard galleys. Practices of repairing and individualising bowls further mirror those of the restricted economy of the seaborne environment; the presence of at least one bowl bearing decorative scratch marks suggests artistic aspirations beyond the simple denoting of ownership (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Ceramics from the Inquisition prison at Malta: a) imported dish; b) part of a Maltese ceramic brazier; c) Maltese water jug; d) small imported cooking pot, sooted on underside (figure by R. Palmer).

Figure 7. Remains of lanterns and a saucer lamp from the Inquisition prison at Malta (figure by R. Palmer).

Figure 8. Sherd of a Maltese bowl, decorated internally and externally (figure by R. Palmer).

Prison walls offer a stable surface into which inmates could carve. Early modern graffiti are relatively abundant in Malta and frequently found carved into the walls of churches and other buildings. Webster's (Reference Webster2008: 118) reminder to Roman archaeologists that “individuals at all levels of Roman society” produced graffiti is pertinent here, and should caution us against attributing all graffiti in the Inquisitor's prison to the galley rowers. Nevertheless, isolating graffiti pertaining directly to incarcerated oarsmen is potentially more secure than specifying particular finds from artefact assemblages. Several graffiti at the Birgu prison depict Islamic iconographic features, including interlocking circles, raised hands and flowers, specifically the rose and tulip: roses represent the Prophet Muhammad and tulips the creator God, the Ottoman Empire or both (Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 185). The walls also bear several Arabic inscriptions that, although not extensively studied, all appear to relate to prayer and quote from the Qur'an (Figure 9). The association made by the Inquisition between Muslim slaves and sorcerers, however, means that the use of these inscriptions in religious incantations cannot be ruled out (Ciappara Reference Ciappara2001: 90). Some inmates carved their names, including two convict rowers (Figure 10): Angelo Rooca spent ten months confined in 1761, after the Inquisition arrested him for sorcery; a decade earlier, Leonardo Palumbo served seven and a half months on the same charge (Ciappara Reference Ciappara2001: 525–31).

Figure 9. Two rose graffiti from the Inquisition prison in Malta; the upper one is accompanied by an Arabic inscription and the lower by a tulip (figure by R. Palmer).

Figure 10. Stone-carved sundial high on the south-west wall of the prison courtyard, bearing the name “LEONARDO PALOMBO”; Inquisitor's palace, c. 1750 (figure by R. Palmer).

For captives, writing one's name or inscribing something associated with one's natal religion—which your captors may consider heretical—are strikingly empowering and re-humanising acts. The extant graffiti at Birgu, however, show no evidence of censure or erasure. In reality, such acts were tolerated in the Inquisitor's prison because they were also tolerated in broader society (Palmer Reference Palmer2021: 183), being more commonplace than we might sometimes assume. Historians endeavour to remind us that servitude in the early modern Mediterranean was “understood in terms of religion and mischance, not race and destiny, as in New World servitude” (Weiss Reference Weiss2011: 3). When contrasted with transatlantic slavery, this can certainly seem to be the case. Yet the multifarious states of captivity experienced on board a Maltese galley also demonstrate that while religion was very important, rowers were not simply “confessionalized captives” (Salzmann Reference Salzmann2013: 395). Such notions neither account for Catholics forced into servitude on the Knights' galleys alongside Muslims, Jews and other Christians, nor explain the tolerance of the captor's society of non-Catholic religious worship by rowers when on land.

Conclusion

For nearly 300 years, Malta formed part of a Mediterranean pattern of mobility in which piracy and slavery became linked (Greene Reference Greene2010: 79–80). Through slaving, the utilisation of captives for galley-rowing, and the building of coastal watchtowers to protect Maltese inhabitants from a similar fate, the Knights engaged in and with processes of captivity that spread across the region. Any picture of the early modern Mediterranean that excludes the contributions of captives, and the ramifications of captivity on daily mobility and security, offers a skewed and inaccurate image. Life at sea and on land had many different restrictions for captives—both physical and social. Eating practices differed, with more socially engaged communal eating on land, compared with enforced eating with one's galley bench-mates. The marking and individualisation of bowls in both maritime and terrestrial contexts indicates limited property ownership, which possibly included objects for personal grooming. Gaming appears to have been ubiquitous, with dice and stone counters fashioned out of refuse and pebbles allowing captives to socialise not only on land, but also with their bench-mates at sea.

Galley rowers maintained many religious and cultural customs while engaging with and influencing the captor society. Christians and Muslims imprisoned for sorcery demonstrate interaction with the local people who engaged their services—an interaction that positions them as potential agents of social change—as well as with those who denounced them, while captives in the bagno sold the goods they produced. Far from being denied religious freedom, Muslim slaves had their own mosques and religious leaders, and their overtly religious graffiti were not deemed sufficiently threatening for the Inquisition to erase them. Scholars too readily forget the early modern connections and relationships between North Africa and Europe (see Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith2015: 24); the Maltese example presented here should not be surprising. Perhaps the historical metanarrative of religious war between the Crescent and the Cross has been too prevalent in our image of early modern Mediterranean cultural interactions.

Captives and the material ramifications of captivity are visible if we approach the archaeological record with the appropriate level of sensitivity. We do not need to excavate new sites, or be so fortunate as to discover direct evidence in order to identify past captives. We do, however, need to work with the archaeological record. Freely employing broader categories more suited to archaeological investigation (e.g. galley captives) de-shackles my investigation from the specific pursuit of slaves, convicts or debtors—the finer-grained classifications borrowed from historians. By shifting the focus onto captivity as a process that occurs within and alongside wider social phenomena, we can start to follow the material traces of captives, their interactions with each other and non-captives, and their cultural influences on captor societies in everyday settings. Such an approach makes the re-examination of previously studied sites and assemblages not only a highly productive venture, but also essential if we aim to tell a story of the past that includes captives and the consequences of their captivity.

Acknowledgements

The primary research for this article was carried out at the Inquisitor's Palace Museum and Malta Maritime Museum, and I thank the respective curators Kenneth Cassar and Liam Gauci. I am grateful to Timmy Gambin for sharing his original research findings and to Antonio Fornaciari. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers, who provided helpful feedback.

Funding statement

Research in Malta was financially supported by the Research Foundation-Flanders (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, grant K20815N) and Ghent University (Commissie Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek).