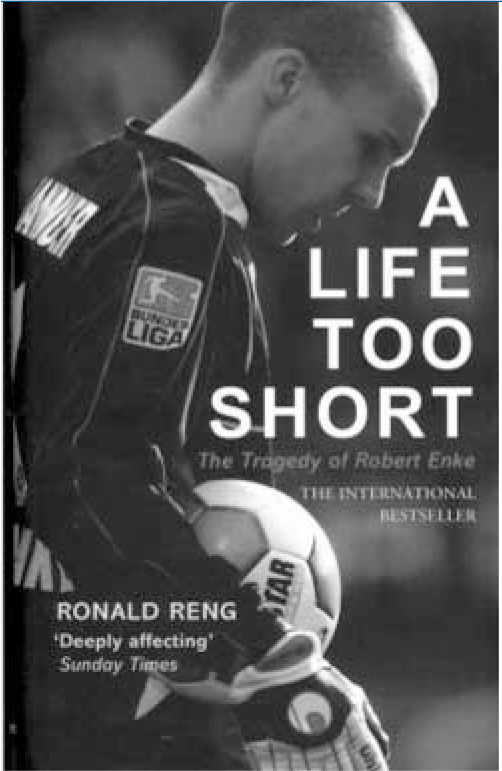

In late 2009, Robert Enke was at the peak of his footballing powers, acknowledged as one of the German Bundesliga's best goalkeepers and expected to represent his country in the 2010 World Cup. He had seemingly overcome personal tragedy, depressive episodes and a series of ill-fated foreign transfers, regaining the form that had previously linked him with some of the biggest clubs in the world. On 10 November 2009, Robert Enke ended his life, aged only 32. Over 40 000 people attended his memorial service.

A Life Too Short was originally intended to be a collaboration between Enke and his friend, author Ronald Reng; not an autobiography, but a chronicling of how Enke had managed and overcome his depression. The book is an intimate portrait of a man who appears to be the antithesis of our description of the modern international football player; a reserved, thoughtful and dignified individual, who married his childhood sweetheart and for whom manners and respect were more important than money or trophies. Indeed at times, the reader could be forgiven for wondering whether Enke's untimely death and the writer's close relationship to his subject has led to a somewhat rose-tinted portrayal of him.

Reng's previous bestselling book, The Keeper of Dreams, explored the unique physical and psychological characteristics of a professional goalkeeper compared with his outfield counterparts, and A Life Too Short often reads like a case in point. The trained reader can identify a number of cognitive biases that dogged Enke, such as the selective abstraction that he often applied to individual performances.

The player's private struggle with such thoughts runs parallel with the matches, tournaments and transfers that many readers will be familiar with, lending an insight into aspects of football, particularly the art of goalkeeping, that some would not have previously considered. The subtle development of Enke's skills, observed beautifully by the author, and his growth in stature among his peers are in stark contrast to the player's confidence in his own abilities, illustrated by excerpts from his diary and from interviews with Reng.

As one would expect, the book is less accessible to those who are not fans of the sport, not least because Enke's attention to detail and enthusiasm for the minutiae of goalkeeping is reflected in Reng's writing. Although many of the characters described outside of the sport are colourfully depicted by the author, it is the portrayal of many of Enke's contemporaries and their impact on his game that is most interesting to the football supporter. Some personalities in the game are reflected very badly in their lack of understanding of both Enke's mental illness and the difficulties some young players have in adjusting to new teams, countries and languages.

Critics will draw attention to the frequent use of the word ‘depressives’ to describe those with depression, but by and large the book addresses mental health issues in general with both sensitivity and rationalism. Although Enke's recovery from depressive episodes is inspiring, the spectre of his suicide looms large over much of the book, and the less-informed reader could be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that his eventual suicide was inevitable.

At the very least, A Life Too Short shines a spotlight on what must be a more prevalent issue than is currently recognised – that of mental illness in professional footballers. It begs the question why few cases are reported in British football leagues and whether or not it will take a tragedy like the death of Robert Enke for the sport in this country to recognise its presence.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.